ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — First, there were micromachines — actually, microengines — each about the size of a grain of sand.

Now there are microtransmissions.

Fabricated for the first time by researchers at Sandia National Laboratories, these remarkably augment the power of the tiny engines.

A visitor interested in scale looked through a microscope to see a spindly, one-millimeter-thick Allen wrench passed over a microtransmission. The sight resembled the huge alien space ship darkening and then covering New York in the movie “Independence Day.”

Despite its tiny size — like a microengine, about that of a grain of sand — a microtransmission can increase the power of its microengine by a factor of 3 million, theoretically generating enough force to move a one-pound object, say researchers Steve Rodgers and Jeff Sniegowski.

“We believe this is by far the most force ever generated by a polysilicon micromechanical device,” says Rodgers. “We’re showing that you can move significant loads and get the function you want.”

Microtransmissions operate on the same principle that allows a multigear bicycle to be pedaled up a steep hill more easily than a single-speed bike: No more input force is used, but the force is applied over a shorter portion of the wheel’s turn. The new distribution of energy slows the bike but magnifies the force because it is concentrated over a shorter distance.

The robust micromachines may be effective in satellites, where minimizing payload weight is important. Other possibilities include sensors that can communicate with each other aboard an aircraft, and in optical telescopes and optical switching for telephone lines. Microsurgical applications, which require relatively large forces on very small areas, are another possible area of application.

While Sandia, a laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), is interested in the tiny machines as near-invisible locks for nuclear weapons, companies and universities who wish to utilize the modular technology for fabrication purposes will be able to download basic units of the transmission “as easy as clip art,” says Rodgers.

Having downloaded the blueprint for the gears, a company can design as few or as many intermeshing transmission systems as needed merely by duplicating and moving the basic gear arrangement. This can be done cheaply and easily on commonly available computer automated design programs. “In general, people needing this technology would use much lower gear ratios than 3 million:1, since the power and precision that this demonstration assembly offers would be required only in very special cases,” says Rodgers. “But since the assembly is modular, they can easily do as little or as much as they’d like.”

Sandia in the recent past has licensed micromachine technology to private industry to build cheaper, more effective air bag sensors in cars, as well as to create newer anti-skid technologies than those currently being developed in the auto industry.

Why the microtranny?

Micromachines need power in larger amounts than first thought necessary because of the adhesion and static friction — together termed ‘stiction’ — that a stationary gear must overcome in order to begin movement.

One reason for stiction is that after a gear is etched out of silicon, the surface of the silicon oxidizes — in a sense, rusts — into glass, which binds microaxles or microgears to stationary surfaces surrounding them. “Even minute amounts of water vapor and outgassing from epoxies can be significant in blocking the startup action of a microgear,” says Sniegowski. “Power is needed to overcome that resistance.”

The new device also should benefit basic engineering research, says Sniegowski. “Micromachine science does not yet understand how to deal with the effect of friction on machines that are so small,” he says. “To study how these effects and others operate, you’ve got to be able to apply a significant level of force. Now we can apply these forces in fundamental tests to determine qualities such as a micromaterial’s fracture strength.”

Another peculiarity of the microrealm is the difficulty of developing a clutch to change gears. In automobile transmissions, gears keep turning through inertia when a clutch disengages, and so synchronization with a replacement gear is possible. But to have inertia, an object must have mass, and for practical purposes, microgears — each approximately the diameter of a human hair — have no mass. For this reason, they can be accelerated very quickly, reaching velocities of several hundred thousand revolutions per minute in a few tenths of a second, but as soon as power is removed, stop dead.

“Automobiles,” says Paul McWhorter, one of the leaders of the Sandia micromachine effort, “have a much lower range of operating speeds.”

Other problems involve building an interface with the macrorealm when the amount of power transmitted may vary over several orders of magnitude.

A positive possibility is that the microtransmission may one day provide accurate displacements on the atomic scale. One revolution of the demonstration drive gear generates a calculated displacement of the output gear of only 0.8 angstroms — the same unit of measurement normally used to determine spaces between atoms. One can see, in Sandia videos, the odd sight of a drive gear spinning at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute, with succeeding gears each turning more slowly and presumably more powerfully until, at the end, almost no motion is observed.

Layout and fabrication

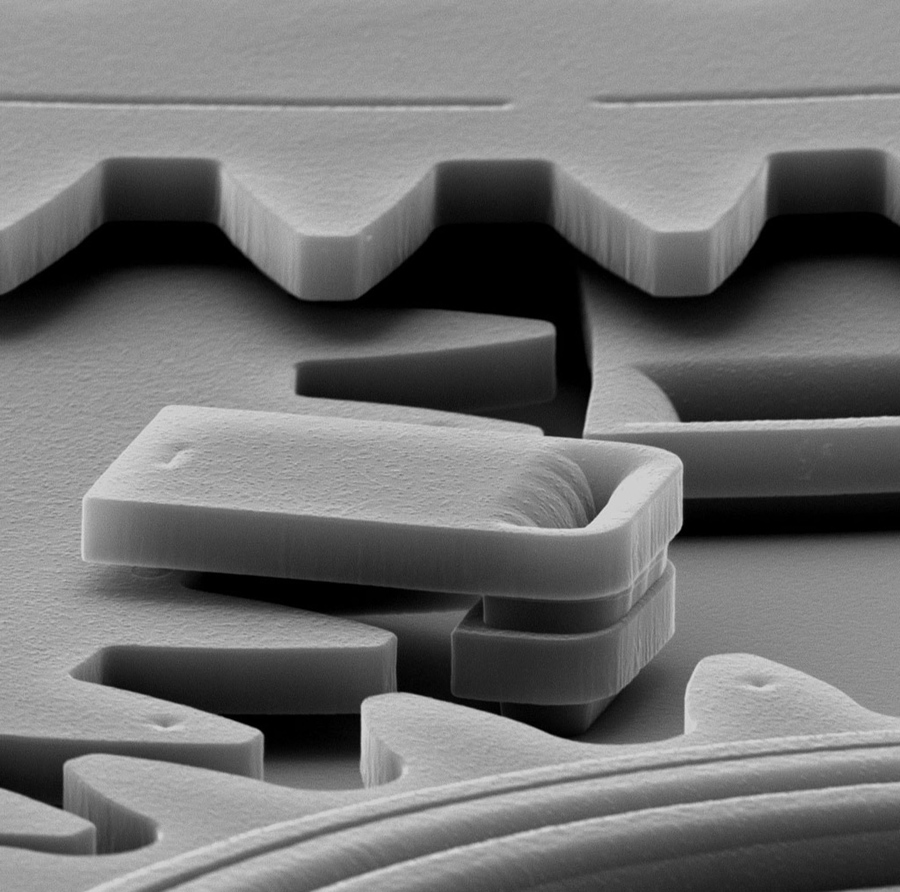

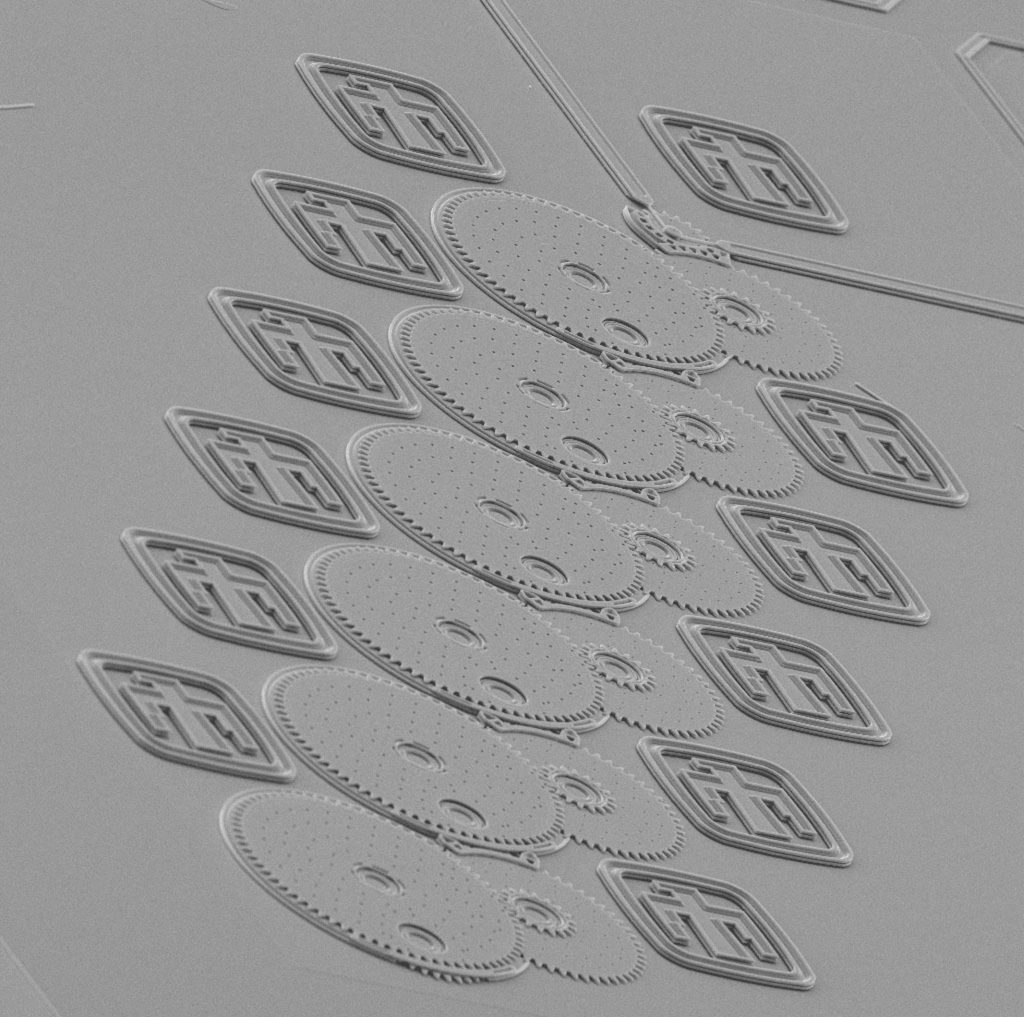

The 3 million:1 Sandia microtransmission comprises six identical transmission systems, each with two dual-level gears. The two gears, crafted one atop the other, operate at ratios of 3:1 and 4:1, which together form a 12:1 gear reduction ratio. A coupling gear allows more gear sets to be added modularly.

In less than one square millimeter of area, through use of 29 intermeshing gears, the transmission achieves a 3 million:1 gear reduction ratio . The gearing is reversible, and so can increase speed as well as decrease it. The gearing is driven by a five-level micromachine, believed (like the transmission) to be the most advanced motor of its kind in the world. Like its earlier siblings, it is powered by comb drives, but these new drives are thicker and stronger.

According to Roger Howe, director of the University of California at Berkeley’s Sensor and Actuator Center, “Sandia’s five-level polysilicon technology enables lots of new devices, including the transmission. The most powerful thing is that they can do five levels.” The Berkeley lab is one of the original founts of micromachining.

Micromachine “levels” refer to the tiny elevations that separate a gear or row of comb “teeth” in order that they may move freely. This is achieved by etching away so-called “sacrificial” oxide layers. The creation of additional levels permits thicker and therefore stronger comb drives. It also allows more gears to overlap each other, compressing the amount of horizontal space needed. While other laboratories have built three-level machines, there is no known competitor to the Sandia five-level machines, which require sophisticated design and processing knowledge.

Each drive consists of two tiny comb-like structures, with teeth of one lying between the teeth of the other. By alternating tiny electric signals to the combs, they attract each other to one side and then the other. The motion is transmitted to a tiny piston-like linkage moved by one of the combs.

A second comb drive provides power at right angles to the first. The piston it drives, when timed with the force of the first piston, is sufficient to turn a drive wheel on the microengine.

The fabrication method has been used to create previous generations of four-level Sandia micromachines that spin at hundreds of thousands of revolutions per minute.

Sandia is a multiprogram DOE laboratory, operated by a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corp. With main facilities in Albuquerque, N.M., and Livermore, Calif., Sandia has major research and development responsibilities in national security, energy, and environmental technologies and economic competitiveness.

Technical contacts:

Paul McWhorter, mcwhorpj@sandia.gov, (505) 844-4683

Steve Rodgers, rodgersm@sandia.gov, (505) 844-1784

Jeff Sniegowski, sniegojj@sandia.gov, (505) 844-2718