Nanoscopic discovery may have implications for smog, asthma, cloud formation

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — To stretch a supply of salt generally means using it sparingly.

But researchers from Sandia National Laboratories and the University of Pittsburgh were startled when they found they had made the solid actually physically stretch.

“It’s not supposed to do that,” said Sandia principal investigator Jack Houston. “Unlike, say, gold, which is ductile and deforms under pressure, salt is brittle. Hit it with a hammer, it shatters like glass.”

That a block of salt can stretch rather than remain inert might affect world desalination efforts, which involve choosing particular sizes of nanometer-diameter pores to strain salts from brackish water. Understanding unexpected salt deformations also may lead to better understanding of sea salt aerosols, implicated in problems as broad as cloud nucleation, smog formation, ozone destruction and asthma triggers, the researchers write in their paper published in the May Nanoletters.

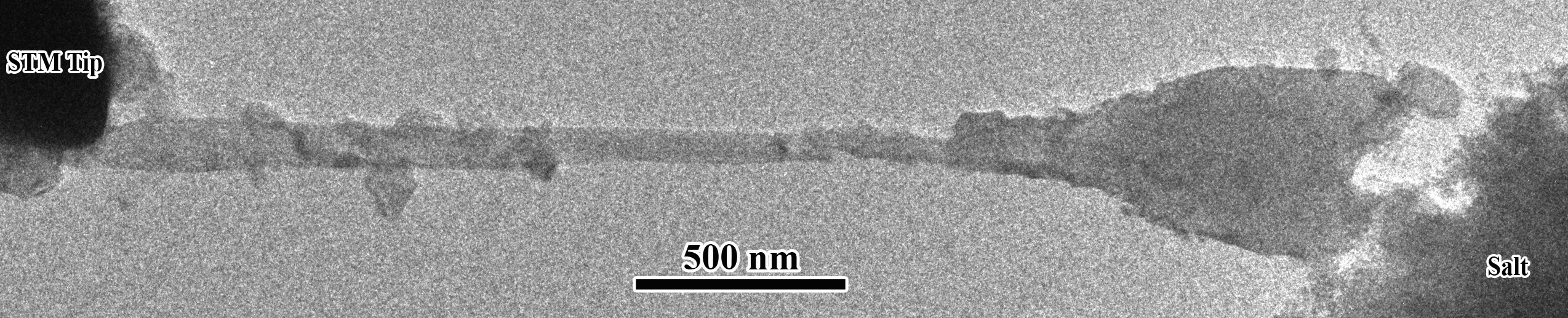

The serendipitous discovery came about as researchers were examining the mechanical properties of salt in the absence of water. They found unexpectedly that the brittle substance appeared malleable enough to distort over surprisingly long distances by clinging to a special microscope’s nanometer-sized tip as it left the surface of the salt.

More intense examination showed that surface salt molecules formed a kind of bubble — a ductile meniscus — with the exploratory tip as it withdrew from penetrating the cube. In this, it resembled the behavior of the surface of water when an object is withdrawn from it. But unlike water, the salt meniscus didn’t break from its own weight as the tip was withdrawn. Instead it followed the tip along, slip-sliding away (so to speak) as it thinned and elongated from 580 nanometers (nm) to 2,191 nm in shapes that resembled nanowires.

A possible explanation for salt molecules peeling off the salt block, said Houston, is that “surface molecules don’t have buddies.” That is, because there’s no atomic lattice above them, they’re more mobile than the internal body of salt molecules forming the salt block.

Salt showing signs of surface mobility at room temperatures was “totally surprising,” said Houston, who had initially intended to study more conventionally interesting characteristics of the one-fourth-inch square, one-eighth-inch-long salt block.

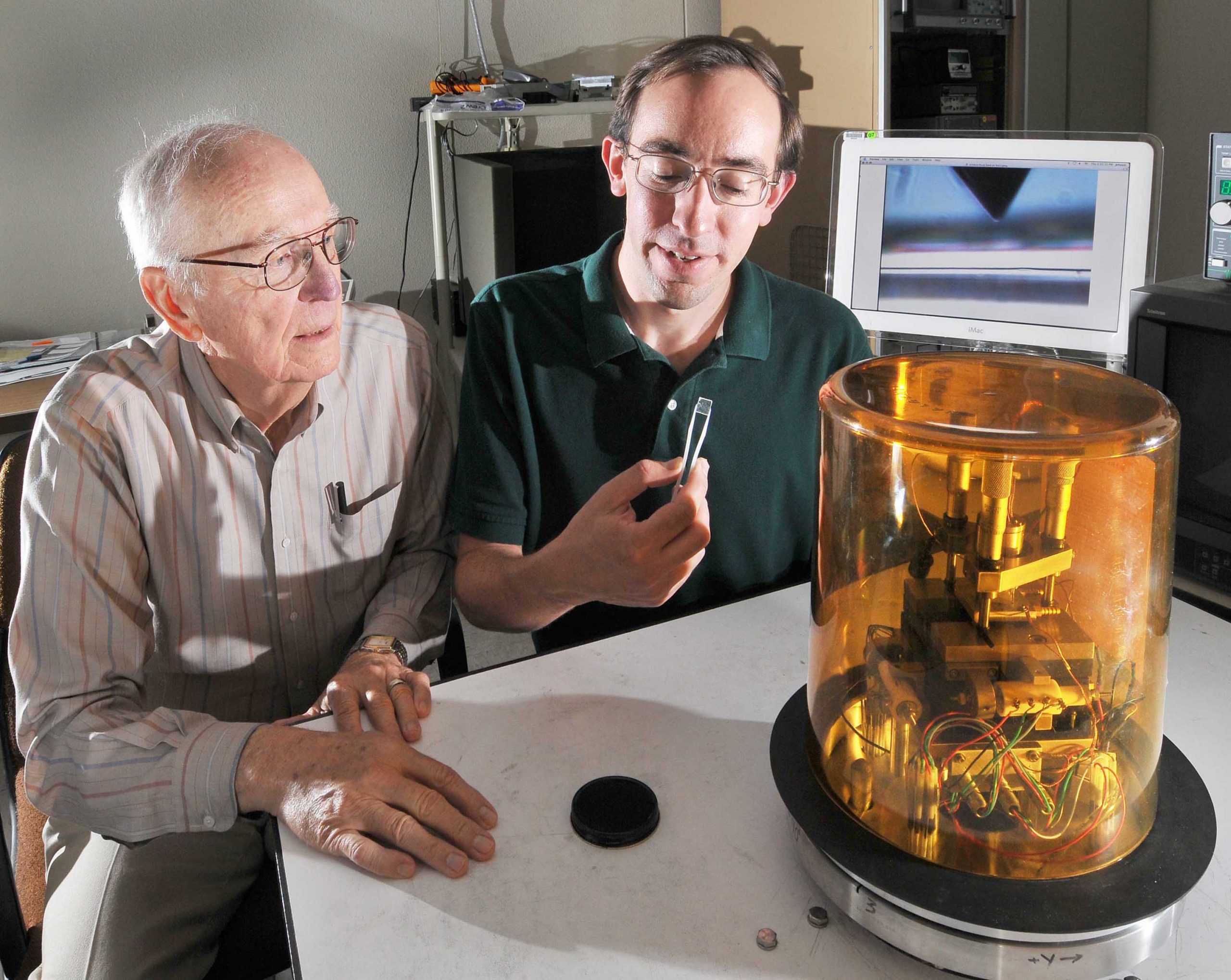

Other researchers on this work include Sandia’s Nathan Moore and Jianyu Huang, with Junhang Luo and Scott Mao from the University of Pittsburgh.