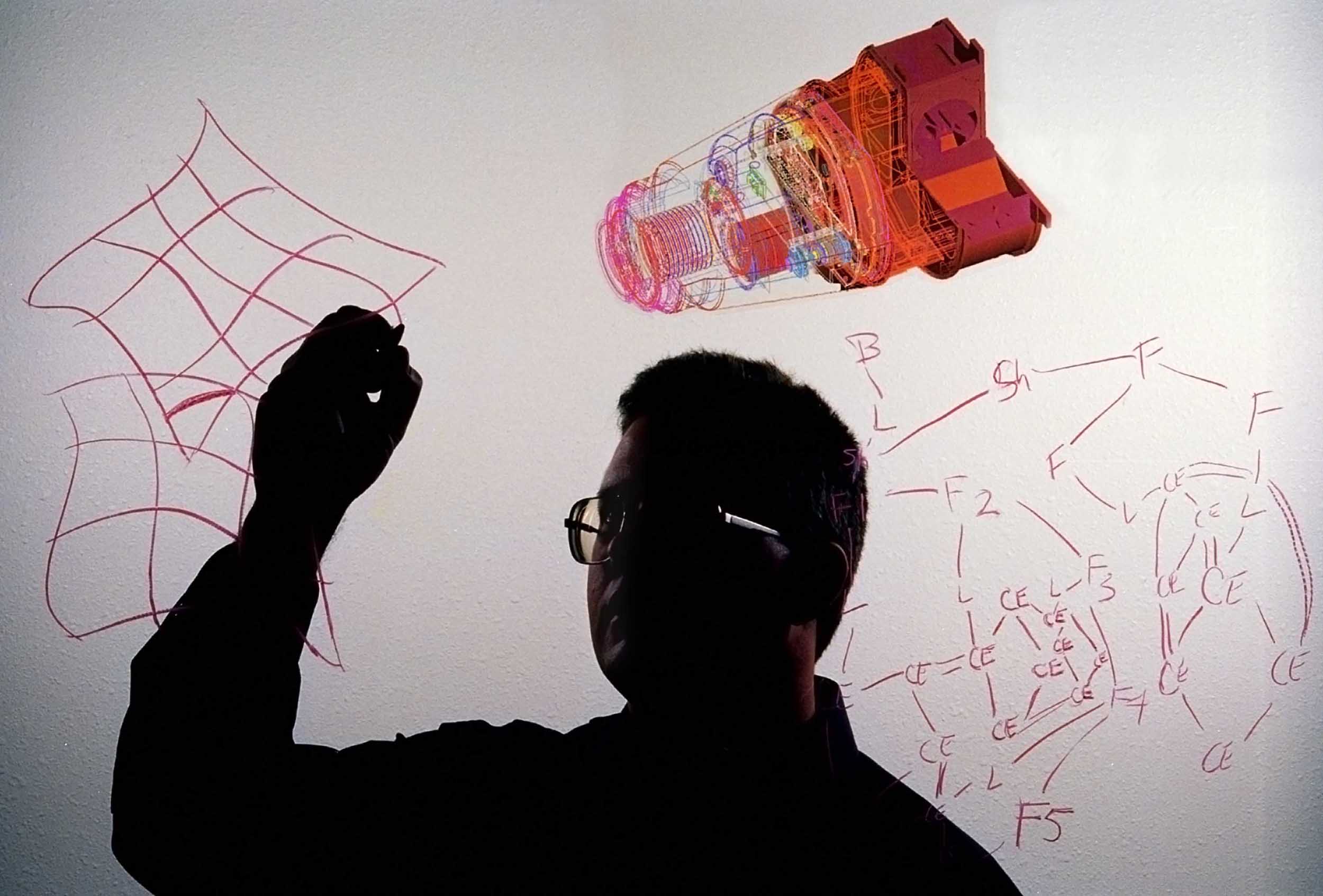

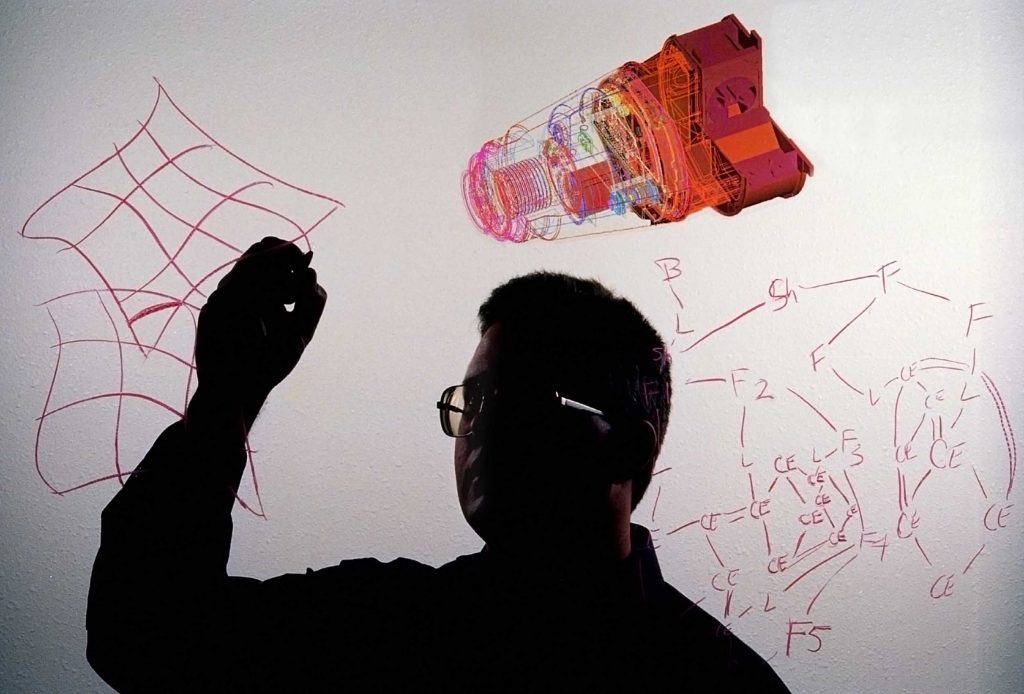

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. —What’s the best way to solve a wicked problem — by working in a large group sharing ideas via the intranet or as individuals? That’s the question George S. Davidson and his research team at Sandia National Laboratories attempted to resolve this summer.

The research, conducted by Davidson, Courtney Dornburg, Susan Stevens, Stacey Hendrickson, Travis Bauer and Chris Forsythe, had some surprising results.

“In this day and age of email and the internet, our expectations were that computer-mediated group brainstorming, i.e. across the web with no face-to face contact, was going to have the best results,” Davidson says. “What we found, however, was that people working as individuals were at least as effective and possibly more so than those brainstorming in a group over the web when trying to solve ‘wicked,’ tangled problems, both in terms of quality and quantity.”

The experiment was funded by Sandia’s internal Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program.

Wicked problems are those problems that by their very definition are so tangled that there is no agreement about their definitions, much less their solutions.

Davidson assembled a team that consisted of himself, three psychologists (two of them PhD students), and two cognition researchers to investigate tools and methods for bringing very large numbers of people together to solve difficult problems via the intranet. The team anticipated that the group brainstorming could result in a huge pool of ideas that might lead to solutions. They decided to pursue an electronic brainstorming experiment built around the very common face-to-face technique used at Sandia where people submit ideas written on Yellow Sticky Post-It ® Notes.

Sandia is a National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) laboratory.

As the team designed the experiment, the initial issue was deriving a wicked problem with no predefined “right or wrong answer,” Dornburg says. In June Dornburg, a psychologist who has worked at Sandia for two years, attended a new-hire breakfast hosted by Labs President and Director Tom Hunter. During the breakfast, Hunter posed the new hires with a challenge, asking them to think about the implications of two popular models in management theory. In one view workers are just another natural resource to be used. In contrast, the second model sees employees as assets, which can be made more valuable by investing in their development. Dornburg shared the question with the team, and they unanimously decided to make it the wicked problem for the experiment.

They recruited 120 Sandia employees and contractors and 26 student interns through an internal online daily newsletter and word of mouth to participate in the experiment that lasted four days in August. The participants were broken into two groups, those who worked alone and did not see the ideas of the other participants and those who worked in a group and were able to see and build on the ideas of the other members in the group via the Labs’ intranet. Of the 120 employees and contractors, 69 contributed ideas.

During the experiment, participants logged onto the website anonymously and saw the question displayed at the top of the screen. They were asked to input their ideas — the more the better, but no name calling or abusive language.

The research was unusual because, while studies have been conducted with large brainstorming groups, most have been performed in academic settings with college students as participants. This experiment was, to the research team’s knowledge, the first done in a laboratory/industrial setting over an extended period of time.

In addition, most previous studies looked only at quantity — number of responses — while only a small number examined the quality of the ideas. The Sandia experiment analyzed both. Responses to Hunter’s question were scored by team members according to originality, feasibility, and effectiveness. Responses were also analyzed by STANLEY, a Sandia-developed text analysis tool that looked at common noun phrases and key words.

“We were amazed at the length and quality of the responses, both from the people working as a group and those working individually,” Dornburg says. “People were very engaged, often writing long, detailed responses.”

She adds that what was most interesting is that the quality of ideas from the people responding as individuals was “significantly better across all three quality ratings.”

Dornburg says the finding that individuals are more successful than groups in computer-mediated brainstorming suggests a time- and cost-saving potential for companies. Generally, when electronic group brainstorming is compared to face-to-face brainstorming, it is touted as having the advantages of shorter meetings, increased participation by remote team members, better documentation via electronic recording, and cash savings. But the Sandia research suggests that people working to solve problems on their own might involve less time and, thus less expenses, than electronic group brainstorming.

While individuals working alone nominally faired better in this study, Davidson says, the research also indicates that group on-line brainstorming can be effective when ideas are needed from large numbers of people.

“Despite our findings, it still seems reasonable that there may be modes of [as yet, untested] web-based interactions and strategies that would allow the larger group to have superior performance compared to a limited number of participants working alone, even if those participants are able to reason and write about their ideas with brilliance and clarity,” Davidson says.

He expects that in coming years “better software, including threaded discussions with moderators to focus the work and prediction markets to evaluate quality, will become tools that large organizations will use to solve wicked problems.”