ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Diamond-like carbon films created at Sandia National Laboratories are helping probe the far boundaries of the solar system as part of a NASA mission to study how the sun’s solar wind interacts with the interstellar medium – the matter that exists between the stars within a galaxy.

The films are in the low-energy sensor (IBEX-Lo) on board NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), which lifted off in October on a mission to study the farthest fringes of the solar system. IBEX’s two bucket-sized sensors, covering high and low energy ranges, are designed to capture particles bouncing back toward Earth from the distant boundary between the hot wind from the sun and the cold wall of interstellar space.

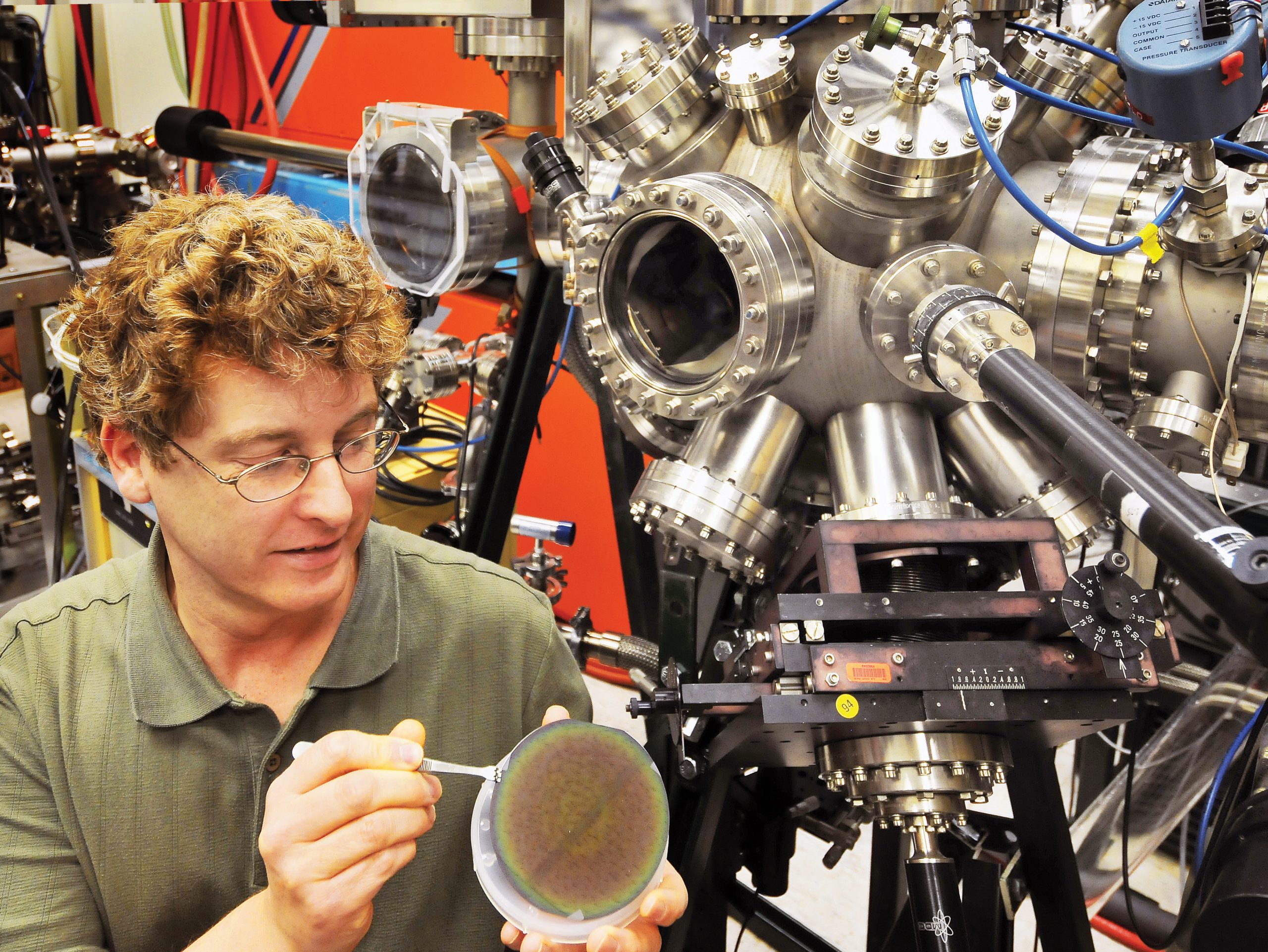

The active conversion surface of the low-energy neutral atom detector is coated with Sandia’s diamond-like films created by Tom Friedmann.

“The primary purpose of the diamond-like carbon films is to provide a surface that will ‘efficiently’ ionize energetic neutral atoms,” Friedmann says, “so they can then be detected. Smooth surfaces are required so that the scattered particles can be efficiently collected. If the surface is rough, scattered particles are lost, decreasing efficiency. The diamond-like carbon films have an average surface roughness that is about one angstrom. This is less than the diameter of a carbon atom.”

To create the 30 films aboard the system, Friedmann used pulsed-laser deposition to deposit the films on the conversion surfaces. Carbon was used because it has relatively high conversion efficiency, low sputter yield, and is very smooth, he says. Single crystal diamond has the highest efficiency but is too expensive to grow over large areas and difficult to polish to the extremely low surface roughness needed. The diamond-like carbon films naturally grow smooth and require no polishing.