Download 300dpi JPEG image, ‘henson.jpg’, 881K (Media are welcome to download/publish this image with related news stories.)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories and the University of Kentucky are developing enabling technologies for a new thin-film, ultralight deployable mirror that may be the future of space telescopes and surveillance satellites.

Made out of a “smart” material that changes shape when struck by electrons fired by a computer-controlled electron gun, it is a whole new approach to space mirrors.

“Unlike the Hubble and the upcoming NASA Next Generation Space Telescope [NGST], which use the traditional polished glass mirror approach, this is a light-weight thin film that could be folded up and carried on a small booster rocket and opened to its full diameter in orbit,” says Tammy Henson, principal investigator. “The electron gun would then be used to correct the shape of the film mirror to its desired form to within 10 millionths of an inch that is the required accuracy for optical-quality imaging applications.”

Hubble uses a solid glass mirror, while its successor, the NGST, tentatively scheduled for launch in 2008, may use a mirror constructed from thin glass segments on a composite structure, or even beryllium segments, folded to fit into a launch vehicle.

The new mirror, composed of a piezoelectric material that expands and changes shape when an electric field is applied, relies on a new technique of mirror fabrication. The extremely flexible material can be folded into a small package. When released, it deploys very close to its original state. The material also is extremely light — weighing less than one kilogram per square meter of mirror area compared to 15 kilograms per square meter for the NGST and 250 kilograms per square meter for the Hubble.

Light weight and large-aperture

The light-weight, deployable, and large-aperture aspects of the new mirror approach are what make it attractive for space telescopes and surveillance satellites.

“The next step for NASA after the NGST will be larger mirrors — possibly as large as 20 to 30 meters in diameter — to allow for collection of light from the dimmest and smallest of sources,” says mirror team member Jim Redmond. “It would be nearly impossible to do this with traditional materials because of the expense and the size limitations of launch vehicles. The new technology would allow extremely large mirrors to be launched from small boosters, saving millions of dollars per launch.”

The technology, still in its early stages, has already captured the interest of NASA officials and the remote-sensing community.

“NASA strategic plans call for giant telescopes many meters across and it’s clear we can’t launch large rigid ones,” says John Mather, NGST project scientist. “Hence we will be making a large, flexible primary mirror that will have to be adjusted after launch. One way to improve the performance is to use a small, carefully controlled thin-film mirror located at an image of the primary mirror to correct its error, and such a device might even be useful for NGST. Another way is to make the primary mirror itself adjustable with an electron beam, but this probably will not be ready in time for NGST. This [electron-gun-controlled thin-film mirror] is an example of a device that can be computer-controlled. I think it’s really important to pursue this idea.”

Using electron gun excitation of piezoelectric materials was the brainchild of University of Kentucky researcher John Main.

“Main was developing electron gun technology and was interested in pursuing it for space telescope applications,” Redmond says. “The electron gun eliminates the wires and electrodes used in other ‘smart structure’ approaches that add to the system’s complexity.”

Sandia/University of Kentucky partnership

A partnership developed between the University of Kentucky, Redmond’s adaptive structures group, and Henson’s satellite imaging group.

Under funding from Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program, they have made significant progress in the critical areas of mirror-figure sensing, control algorithm development, electron gun actuation, and space-implementation assessments.

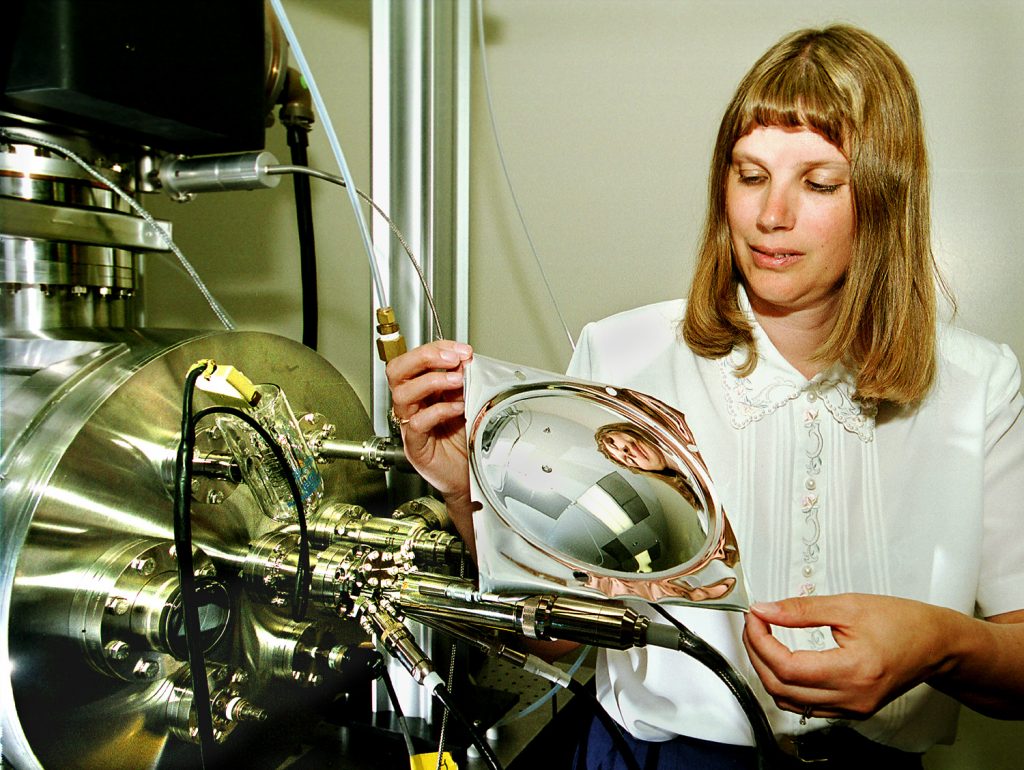

Main, together with PhD student Jeff Martin at the University of Kentucky, are pursuing research on the electron gun, while Redmond is developing precision shape-control algorithms for the piezoelectric mirror. Henson is developing optical concepts and mirror-figure sensing systems for the project.

Henson says that besides being lightweight and relatively inexpensive to launch, the thin-skin deployable mirror has the advantage of being able to be “launched on demand.”

“The mirror could be fabricated and deployed in a matter of months — as compared to many years with the Hubble telescope,” she says.

How it works

During their initial research on the new space mirror material, the Sandia and University of Kentucky researchers are using the piezoelectric material polyvinylidene fluoride because it is inexpensive, readily available, and exhibits the necessary properties. However, for actual space applications where the climate is very hostile, piezoelectric polyimide thin-film material looks very promising.

The flexible nature of the piezoelectric mirror material means it will become misshapen once it is deployed in space. It will need to be reshaped with the electron gun.

Laser optical sensors measure the shape of the mirror surface. This information goes into the control algorithm programmed into the computer, which is connected to the gun. The algorithm determines the excitation profile necessary to change the mirror surface to its desired shape via electron gun excitation. Since the initial mirror shape will be very different from the desired shape, the mirror figure sensing method must have both large dynamic range and high resolution.

The gun fires electrons into different areas of the mirror to make the surface change its shape in either a more convex or concave direction. The new shape remains fixed for several hours to days. Then the beam is reactivated to add or remove the charge to make small corrections to the mirror surface shape.

“An electron gun is the same device that draws a picture on your television screen,” Jim Redmond says. “To reshape the film-mirror, the gun distributes a surface charge at a very high resolution.”