LIVERMORE, Calif. — The city of Dublin, Calif., has experienced a dangerous release of chlorine. A plume is headed east — toward Livermore (site of two national security laboratories), but is also threatening other parts of the Tri-Valley region. Was this the work of a terrorist? A disgruntled employee? Or was it simply an accident? And how will the event impact local, state, and federal emergency response officials?

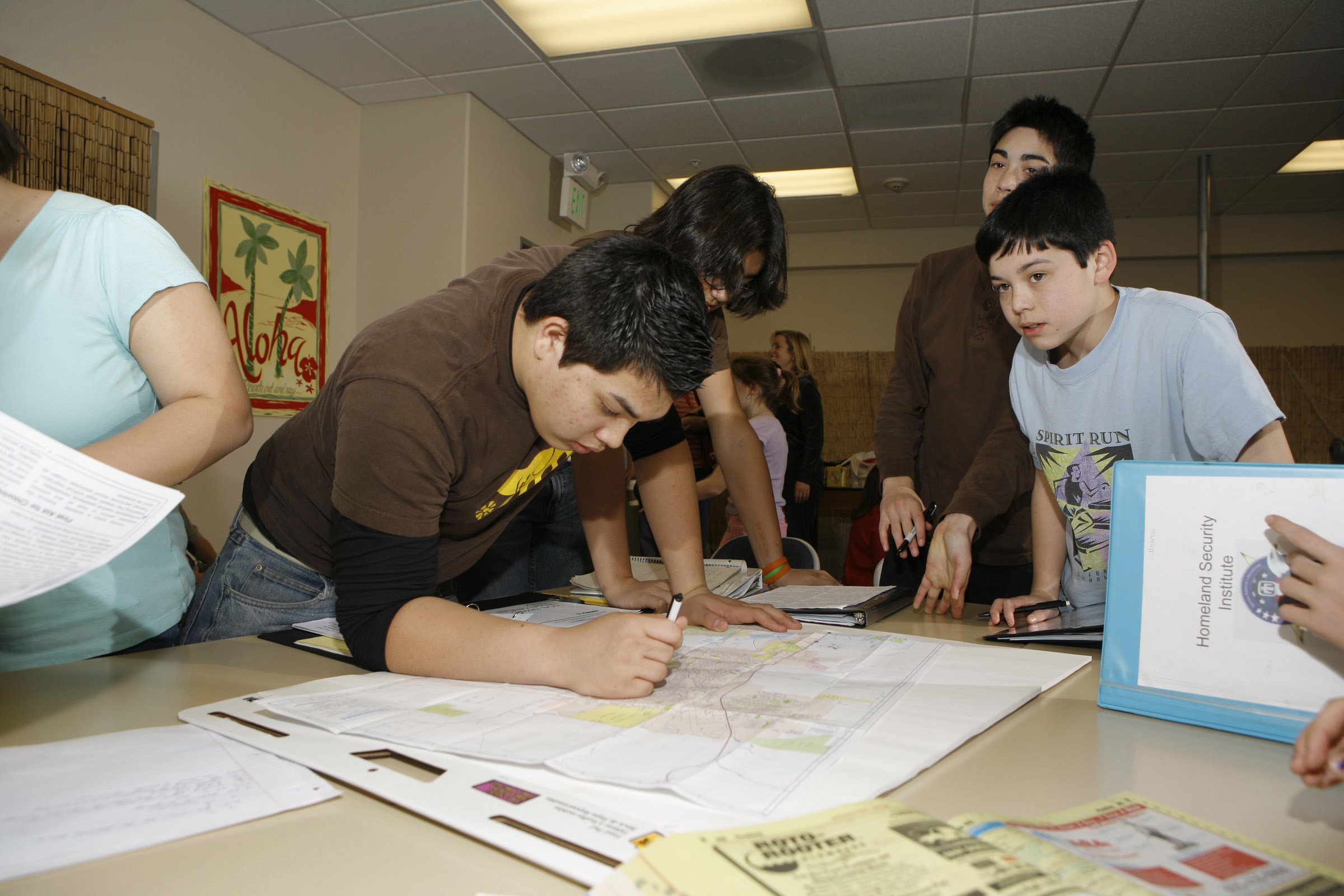

This was the mock scenario presented recently to a group of two-dozen high school and middle school-aged students taking part in Sandia National Laboratories’ High School Homeland Security program.

Sandia is a National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) laboratory.

Conceived in 2005 by Sandia/New Mexico manager John Taylor and initially executed by Taylor, his colleague Annie Sobel, and Sandia/California staff member Michael Johnson (now on temporary assignment in Washington, DC), the High School Homeland Security program has since expanded from its two originating schools (Needles High School in Needles, Calif., and River Valley High School in Mohave County, Ariz.). Hoping to introduce the program to the Bay Area, Taylor asked Sandia/California manager Tim Shepodd to get involved (Shepodd has taught chemistry on a volunteer basis to Livermore High School students and thus had, along with his work managing the lab’s materials chemistry department, applicable experience). Shepodd, whose own children are home-schooled, promptly rounded up a group of some two dozen home-schooled students, received sign-off from parents, and led a six-week course on homeland security and emergency preparedness.

Taylor described the program as “a way to get high-school age students to think outside the box and to recognize the complexities of real-world situations. We have observed that the students who have participated have a lot more confidence when faced with complex problems,” he added. “This type of experience makes them better critical thinkers and more informed citizens and voters.”

Last year, Taylor and two Needles students visited Washington, DC, and briefed Paul McHale, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Security on the program. McHale called it one of the best such education initiatives he’s ever seen, saying he was “deeply impressed by the scenarios and student responses” and suggesting that every high school in the country should have such a program.

During the Livermore class’s final, scenario-based exercise in March, students were split into three groups, representing federal, state, and local officials. To keep things authentic and allow students to experience the chaos and uncertainty inherent in crises, information on the chlorine event came in “dribs and drabs” rather than all at once. Communication between the three groups was clearly an important factor in addressing the fictitious event, but limited by the instructors during the exercise due to lack of resources, dissimilar priorities and needs among each group, and time issues.

“Both the kids and their parents have been exceptionally responsive to the course,” said Shepodd. “They’re learning a great deal about the difficulty and challenges inherent in emergency response, and consequently have developed a much greater appreciation for the professionals charged with those responsibilities.” Tim said the instruction helps sharpen the students’ critical thinking skills, which he says is even more important than the end result of the crisis scenarios. “They (the students) are learning that a planned response is better than an unplanned response, and that it’s important to know the resources and human expertise at your disposal during a crisis.”

“Communication, thinking clearly under pressure, and active listening all apply to real life situations that they (the students) encounter every day,” said Guy Schalin, whose sons Patrick, Kyle, and Brett are students in the Livermore class. “This was a real valuable experience,” added Kyle, 15. “You may want to panic, but you have to stay cool, keep your head, and think things through. It was a stressful situation, so we all needed to keep our composure.”

At the end of the March, the Livermore students will continue their homeland security education by visiting Sandia’s facilities. They are expected to receive program overviews and tours of various laboratories. “Now that the students have gone through a mock-disaster exercise, we want the kids to see where and how homeland security systems and technologies are developed,” said Shepodd. “We want to inspire the next generation of scientists that can keep our country safe in the future.”

In April, the program will take another step in its development when Sandia’s main facility in Albuquerque hosts the first-ever High School Homeland Security Conference. Some 40 students are expected from Livermore, Calif., Needles, Calif., and Albuquerque. In addition to tours of Sandia’s labs, the students will participate in a large role-playing exercise similar to those they’ve studied in their earlier classes.

To date the program has operated on Sandia internal funding provided in part by Sandia’s Homeland Security business unit. Taylor is hopeful of securing additional funding to permit expansion of the program, both in scope and in content. “Realization of Secretary McHale’s vision of having similar programs in high schools across the country is a worthy goal,” he said.