ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — A new type of “smart” machine that could fundamentally change how people interact with computers is on the not-too-distant horizon at the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories.

Over the past five years a team led by Sandia cognitive psychologist Chris Forsythe has been developing cognitive machines that accurately infer user intent, remember experiences with users and allow users to call upon simulated experts to help them analyze situations and make decisions.

“In the long term, the benefits from this effort are expected to include augmenting human effectiveness and embedding these cognitive models into systems like robots and vehicles for better human-hardware interactions,” says John Wagner, manager of Sandia’s Computational Initiatives Department. “We expect to be able to model, simulate and analyze humans and societies of humans for Department of Energy, military and national security applications.”

Synthetic human

The initial goal of the work was to create a “synthetic human” — software program/computer — that could think like a person.

“We had the massive computers that could compute the large amounts of data, but software that could realistically model how people think and make decisions was missing,” Forsythe says.

There were two significant problems with modeling software. First, the software did not relate to how people actually make decisions. It followed logical processes, something people don’t necessarily do. People make decisions based, in part, on experiences and associative knowledge. In addition, software models of human cognition did not take into account organic factors such as emotions, stress, and fatigue — vital to realistically simulating human thought processes.

In an early project Forsythe developed the framework for a computer program that had both cognition and organic factors, all in the effort to create a “synthetic human.”

Follow-on projects developed methodologies that allowed the knowledge of a specific expert to be captured in the computer models and provided synthetic humans with episodic memory — memory of experiences — so they might apply their knowledge of specific experiences to solving problems in a manner that closely parallels what people do on a regular basis.

Strange twist

Forsythe says a strange twist occurred along the way.

“I needed help with the software,” Forsythe says. “I turned to some folks in Robotics, bringing to their attention that we were developing computer models of human cognition.”

The robotics researchers immediately saw that the model could be used for intelligent machines, and the whole program emphasis changed. Suddenly the team was working on cognitive machines, not just synthetic humans.

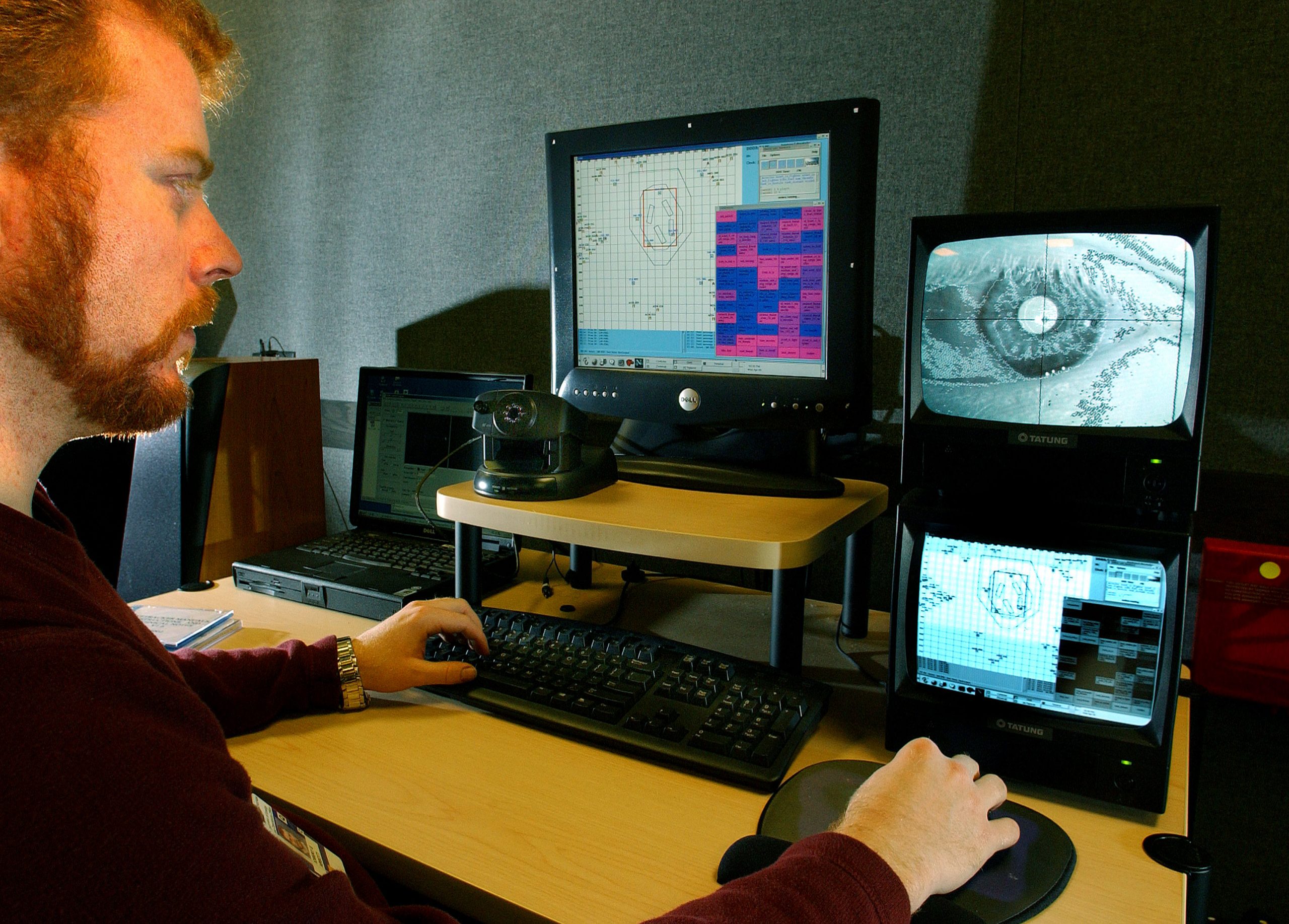

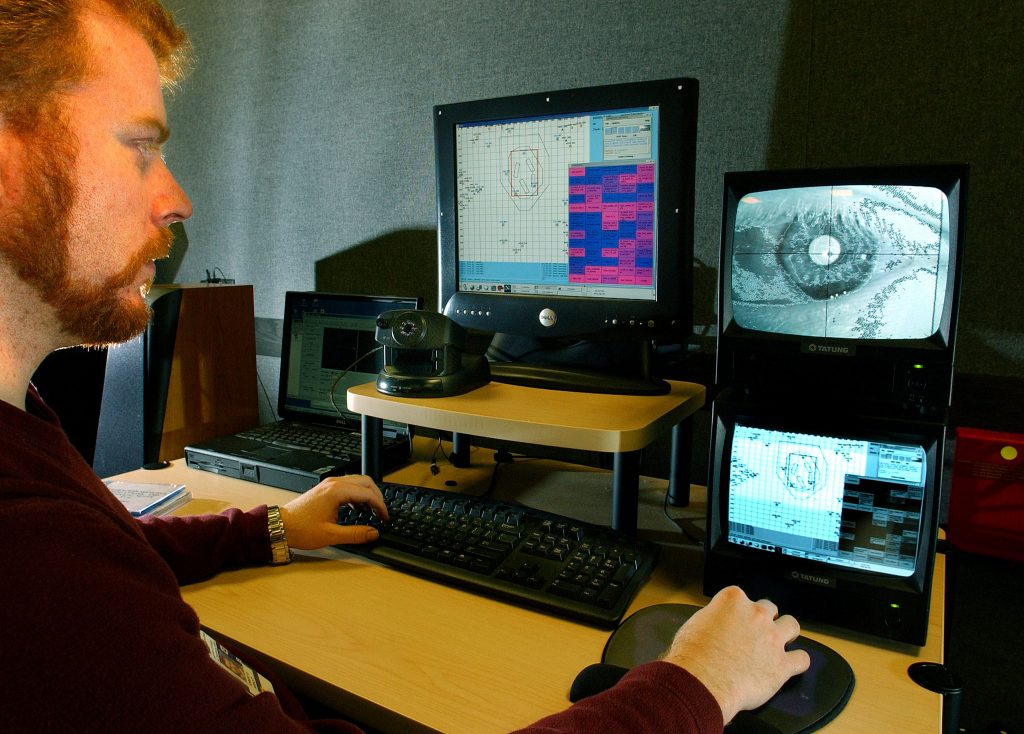

Work on cognitive machines took off in 2002 with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop a real-time machine that can infer an operator’s cognitive processes. This capability provides the potential for systems that augment the cognitive capacities of an operator through “Discrepancy Detection.” In Discrepancy Detection, the machine uses an operator’s cognitive model to monitor its own state and when there is evidence of a discrepancy between the actual state of the machine and the operator’s perceptions or behavior, a discrepancy may be signaled.

Early this year work began on Sandia’s Next Generation Intelligent Systems Grand Challenge project. “The goal of this Grand Challenge is to significantly improve the human capability to understand and solve national security problems, given the exponential growth of information and very complex environments,” says Larry Ellis, the principal investigator. “We are integrating extraordinary perceptive techniques with cognitive systems to augment the capacity of analysts, engineers, war fighters, critical decision makers, scientists and others in crucial jobs to detect and interpret meaningful patterns based on large volumes of data derived from diverse sources.”

“Overall, these projects are developing technology to fundamentally change the nature of human-machine interactions,” Forsythe says. “Our approach is to embed within the machine a highly realistic computer model of the cognitive processes that underlie human situation awareness and naturalistic decision making. Systems using this technology are tailored to a specific user, including the user’s unique knowledge and understanding of the task.”

The idea borrows from a very successful analogue. When people interact with one another, they modify what they say and don’t say with regard to such things as what the person knows or doesn’t know, shared experiences and known sensitivities. The goal is to give machines highly realistic models of the same cognitive processes so that human-machine interactions have essential characteristics of human-human interactions.

“It’s entirely possible that these cognitive machines could be incorporated into most computer systems produced within 10 years,” Forsythe says.

Sandia technical contact: Chris Forsythe, jcforsy@sandia.gov, (505) 844-5720