ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Microneedles measure only two to three times the diameter of human hair and about a millimeter long. But their impact is significant, from helping U.S. service members in the field diagnose infections earlier, to helping individuals monitor their own health.

Sandia National Laboratories is at the forefront of microneedle research and is partnering with others to expand the technology.

A microneedle is a minimally invasive way to sample interstitial fluid from under the skin. Interstitial fluid shares many similarities with blood, but there is still much to learn about it.

“When we started work in this field in 2011, our goal was to develop microneedles as a wearable sensor, as an alternate to blood samples,” said Ronen Polsky, who has led Sandia’s work in microneedles. Microneedles can access interstitial fluid for real-time and continuous measurements of circulating biomarkers.

“People wear continuous glucose monitors for blood sugar measurements,” Polsky said. “We want to expand this to a whole range of other conditions to take advantage of this minimally invasive sampling using microneedles.”

A collaboration between Sandia and an external partner has helped speed up interstitial fluid extractions. That could help get microneedle sensors to the market quicker for other uses including viral detection and electrolyte levels. Sandia recently received a patent for a microneedle sensor that Polsky and his team are trying to commercialize.

“We basically will bring the diagnostic lab to the patient in the form of a wearable device,” he said.

Sandia has current partnerships with SRI, Adaptyx Biosciences and the University of California at Berkeley.

Faster extraction

One of the projects with SRI, an independent nonprofit research institute, has significantly improved the extraction of interstitial fluid.

“The previous technique was highly variable,” Polsky said. “It took one to two hours to get enough fluid to do the analysis.”

That technique involved using four or five arrays of needles, each with five needles.

“Through our new project with SRI, we improved the technique using a single microneedle to get enough fluid for a test in about 10 minutes,” Polsky said. “The new technique works faster, and we get higher volumes of fluid.”

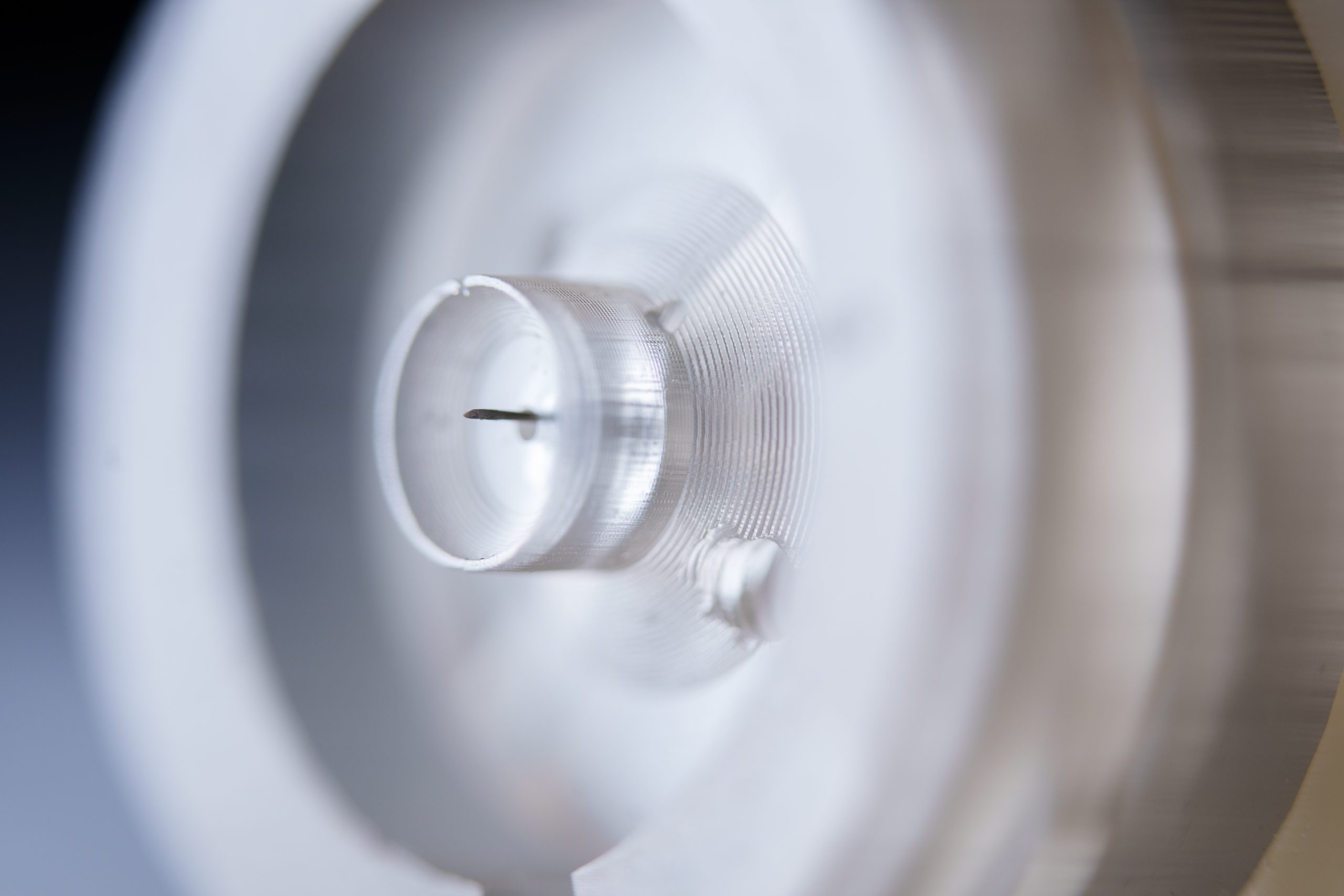

The microneedles penetrate the outer skin layer, but they don’t reach nerve endings and are hollow. Engineers made a couple of changes to improve the extraction technique, including modifying the shape of the needle holders, which are 3D printed at Sandia’s Advanced Materials Laboratory.

“With microneedles, we have engineering and comfort concerns, which play into how we design them,” said Adam Bolotsky, a Sandia engineer. “We get feedback from participants as we’re updating the design. We believe we’ve found the optimal depth for collecting the most fluid with the least discomfort.”

Viral or bacterial?

Will Brubaker is the principal investigator for SRI on the microneedles project. He said improving the interstitial fluid extraction method helps potentially expand the use of microneedles.

“When we collect more samples in a shorter amount of time, we can recruit more people to these kinds of studies,” Brubaker said. “The improvement in the collection method opens up a lot of doors to other applications.”

One such application involves using microneedles to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections. It’s another project that Sandia and SRI are collaborating on.

“Making a distinction as to whether an infection is bacterial or viral would help doctors make informed decisions much quicker to get you treated at the earliest possible stage,” Polsky said.

The Defense Threat Reduction Agency is funding the project.

“It’s a potentially useful diagnostic for a service member who is feeling sick and symptomatic,” Brubaker said, adding that the test is a step toward a device that could perform continuous health monitoring using interstitial fluid. He said there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done before seeking FDA approval.

“There’s a very clear place where this test could eventually be used for the general public,” Brubaker said.

The current work with SRI is expected to wrap up in October.

Adaptyx Biosciences

Sandia is also working with Adaptyx Biosciences under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. Adaptyx is hoping to get a better understanding of what biomarkers are in interstitial fluid.

“We want to broadly understand the components in interstitial fluid and how those components correlate to blood measurements,” Alex Yoshikawa, co-founder of Adaptyx, said. “We’re leveraging Sandia’s existing technology for foundational physiological studies.”

As part of this collaboration, Sandia is extracting interstitial fluid onsite from volunteers using the improved method developed with SRI.

“It’s much easier to recruit volunteers who only need to dedicate 15 minutes of their time versus two hours,” said Sandia’s Brittany Humphrey, who coordinates and oversees the extractions. “The extraction basically requires little to no work on their part.”

Adaptyx is analyzing the fluid collected with the goal of developing continuous monitoring devices for general public use, Yoshikawa said.

Electrolyte sensors

Sandia also has a partnership with the University of California, Berkeley to develop microneedle electrolyte sensors.

“In this case, we are functionalizing the microneedle to be sensitive to electrolytes such as sodium, potassium or calcium,” Polsky said.

Work just started on the second year of the three-year-long project. Continuous electrolyte monitoring, similar to a wearable glucose meter, could help manage cardiovascular functions, hydration levels and electrolyte imbalances for a variety of conditions.

“Studying interstitial fluid is not easy,” Polsky said. “Sandia has made a mark in this area, and we are known as world leaders for this work. It’s turned into this interdepartmental collaborative effort with a lot of other people.”