ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Research at Sandia National Laboratories has shown that it’s possible to predict how well people will remember information by monitoring their brain activity while they study.

A team under Laura Matzen of Sandia’s cognitive systems group was the first to demonstrate predictions based on the results of monitoring test volunteers with electroencephalography (EEG) sensors.

For example, “if you had someone learning new material and you were recording the EEG, you might be able to tell them, ‘You’re going to forget this, you should study this again,’ or tell them, ‘OK, you got it and go on to the next thing,’” Matzen said.

The team monitored test subjects’ brain activity while they studied word lists, then used the EEG to predict who would remember the most information. Because researchers knew the average percentage of correct answers under various conditions, they had a baseline of what brain activity looked like for good and poor memory performance. The computer model predicted five of 23 people tested would perform best. The model was correct: They remembered 72 percent of the words on average, compared to 45 percent for everyone else.

The study is part of Matzen’s long-term goal to understand the Difference Related to Subsequent Memory, or Dm Effect, an index of brain activity encoding that distinguishes subsequently remembered from subsequently forgotten items. The measurable difference gives cognitive neuroscientists a way to test hypotheses about how information is encoded in memory.

She’s interested in what causes the effect and what can change it, and hopes her research eventually leads to improvements in how students learn. She’d like to discover how training helps people performing at different levels and whether particular training works better for certain groups.

The study, funded under Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program (LDRD), had two parts: predicting how well someone will remember what’s studied and predicting who will benefit most from memory training.

Matzen presented the results of the first part of the study in April at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society conference in Chicago. She presented preliminary findings on the second part this summer to the Cognitive Science and Technology External Advisory Board, made up of representatives of universities, industry and laboratories who advise the investment area team managing the LDRD portfolio.

The second part tested different types of memory training to see how they changed participants’ memory performance and brain activity. One of Matzen’s goals is to find out whether recording a person’s brain activity while they use their natural approach to studying can predict what kind of training would work best for that person.

She’s still analyzing those findings, but said preliminary results are encouraging. The computer model from the earlier study was used to predict who would perform best on the memory tasks, and the high performers did even better after memory training.

“That’s promising because one of the things we want to do is see if we can use the brain activity to predict how people react to the training, whether it will be effective for them,” Matzen said.

A next step would be “to use more real-world memory working tasks, such as what military personnel would have to learn as new recruits, and see if the same patterns apply to more complex types of learning,” she said.

About 90 volunteers spent nine to 16 hours over five weeks in testing for the memory training techniques study. Their first session developed a baseline for how well they remembered words or images. Most then underwent memory training for three weeks and were retested.

A control group received no training. A second group practiced mental imagery strategy, thinking up vivid images to remember words and pictures. The final group went through “working memory” training to increase how much information they could handle at a time. Matzen said that averages about seven items, such as digits in a phone number.

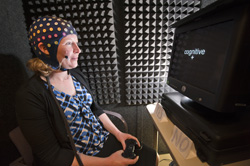

Each volunteer, shut into a sound-proof booth, watched a screen that flashed words or images for one second, interrupted with periodic quizzes on how well the person remembered what was shown.

“It’s designed to be really difficult because we want lots of room to improve after memory training,” Matzen said. The test was divided into five sections, each about 20 minutes long followed by a break to keep volunteers alert.

Each section tested a different type of memory. The first, middle and last sections consisted of single nouns. During quizzes, volunteers hit buttons for yes or no, indicating whether they’d seen the word before. The other two sections combined adjectives and nouns or pairs of unrelated drawings, with volunteers again tested on what they remembered. The image section tested associative memory — memory for two unrelated things. Matzen said that’s the most difficult because it links arbitrary relationships.

When performance was compared before and after training, the control group did not change, but the mental imagery group’s performance improved on three of the five tasks.

“Imagery is a really powerful strategy for grouping things and making them more memorable,” Matzen said.

The working memory group did worse on four of the five tasks after training.

Volunteers trained on working memory — remembering information for brief periods — improved on the task they’d trained on, but training did not carry over to other tasks, Matzen said.

She believes it boils down to strategy: The imagery training group learned a strategy, while working memory training simply tried to push the limits of memory capacity.

While the imagery group did better overall, they made more mistakes than the other groups when tested on “lures” that were similar, but not the same, as items they had memorized.

“They study things like ‘strong adhesive’ and ‘secret password,’ and then I might test them on ‘strong password,’ which they didn’t see, but they saw both parts of it,” Matzen said. “The people who have done the imagery training make many more mistakes on the recombinations that keep the same concept. If something kind of fits with their mental image they’ll say yes to it even if it’s not quite what they saw before.”

The Center for the Advanced Study of Language at the University of Maryland provided the working memory materials for the study Matzen designed. Now, she and the center propose to study tasks that measure cognitive flexibility and how it relates to training performance.

For more information, visit: http://cognitivescience.sandia.gov/.