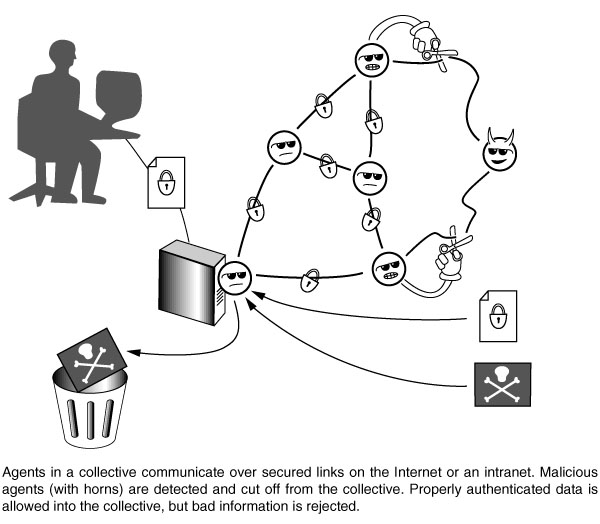

Download 150dpi JPEG image, ‘agents.jpg’, 72K (Media are welcome to download/publish this image with related news stories.)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — In the movie “The Matrix,” malevolent but intelligent security agents — personifications of computer programs able to learn — defend an evil worldwide web.

Now an intelligent software agent wearing a white hat and able to defend itself alone and in groups on today’s Worldwide Web has been created at the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories. Sandia counts among its credentials the fastest computer in the world (ASCI Red) and the fastest home-assembled computer in the world (C-Plant).

“If every node on the Internet was run by one of these agents, the I-Love-You virus would not have got beyond the first machine,” says Steve Goldsmith, lead scientist on the project.

In March, a coalition of these Sandia cyberagents successfully protected five network-linked computers over two full working days of concentrated attack by a four-person hacker force called the Red Team — an expert hacker group, also at Sandia, whose purpose is to test the defenses of government and corporate computer systems.

“We’re less concerned with the teen-aged kid and more with the serious agents from foreign governments or foreign corporations who may take a long time, very gently probing to understand where computers are that they can take over or compromise,” says Goldsmith. “On command, they can be made to act as a supercomputer to attack a target, as happened recently, or crack a privacy code intended to protect financial, medical, or other critical data.”

The cyberagent, still in the laboratory stage, actually functions as a multiagent collective — a distributed program that runs on multiple computers in a network. These could range from artists’ collectives to international corporate computer systems, and from neighborhood shopping groups to an armada of computer-coordinated Abrams tanks.

The program reacts with suspicion to “port scans” that scan all ports — net addresses on a computer that allow entry to different functions — even if the scan takes place over a long period of time, like a year. The “agent” program works by setting up a supra-net collective that constantly compares notes to determine what unusual requests or commands have been received from external or internal sources. Because of this, the system response is not limited to waiting till someone has figured out a defense and put it into a virus checker.

Says Ray Parks, leader of the Sandia Red team, “The biggest problem in the computer world is that new stuff is coming along that you don’t even know exists. Your software doesn’t recognize it. Current defenses work as virus checkers; they recognize only specific virus patterns. But this software will recognize odd attacks. It will turn off services, close ports, go to alternate means of communication, and tighten firewalls.”

What distinguishes the Sandia agent programs from others is that they integrate security functions with normal services — “ftp,” “WWW,” and browsers. “They’re all in each agent. This provides intrinsic security to each user,” says Goldsmith.

The multiagent program is sensitive enough to pick up and store the memory of very faint probes almost indistinguishable from system noise as hackers try to learn enough to take over the computers in a group. Using a sophisticated pattern-recognition system, it can shut down computers in which “Trojan Horses” (secret programs to be operated at a later date by external hostile control) have been installed. It can remove from the network a computer taken over by a hostile insider. And against a runaway barrage of incoming network requests, as recently closed the cyber doors of several American corporations, it can close the gates of the system to prevent it from being flooded with repetitive requests. Among the wary agent’s cybertools are prohibitions on ‘live’ programs such as the I-Love-You virus entering an email system.

No central authority operates the agent. Instead, decentralized control of the algorithm operating each agent makes each autonomous yet cooperative. So, no single point of attack can bring down the collective.

Release of the program for consumer use, Goldsmith estimates, is three years away. “The basic agent program will be ready for specific applications in security-critical businesses and government next year, but the agent must be trained to protect a wider variety of services before it can be used by the average household.”

“Never send a human to do a machine’s job: the cyberagent is a program acting under its own recognizance, and not under the direct control of an operator,” says researcher Laurence Phillips, a member of the group. “Humans aren’t fast enough. A person sitting at a terminal cannot protect you from Internet attack that is coming from everywhere in large masses of data.”

More futuristic uses of intelligent agents involve protecting interplanetary missions that one day may operate robot swarms — cheap multiple robots whose members are expendable — rather than one expensive robot that could render useless the entire mission if it malfunctions. Swarm robots have a vulnerable point: they could be the targets of long-distance hackers. In the case of joint missions, the weakness could make them prey of a nation that might desire failure of the mission for political reasons of its own.

The Worldwide Web will be particularly vulnerable to countries that do not have adequate on-line protection programs, says Goldsmith. “Computers in such countries will become a resource for hackers. If hackers can take up enough nodes, they will have a supercomputer at their disposal that can break commercial codes or mount attacks before people can respond.”

Such laggard countries, says Goldsmith, “may not be popular with other countries and may be pressured by the international community to secure — i.e., inoculate — their systems.

“Ultimately, consumer-level deployment of intelligent-agent programs will replace other programs,” predicts Goldsmith. “Interested consumers or businesses could form secure coalitions against hackers, and they will need to. The home computer is going to be connected to the Internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week with high-speed systems like DSL or cable modem. People will become the target of attacks.”

The multiagent program can also send out probes to locate and figure out the operating system of the attacking force.

“It’s a sophisticated program,” says Goldsmith. “For example, it replaces old agents by fresh agents periodically. This ensures that hacked systems are flushed eventually and must be re-hacked to be compromised.”

A kind of artificial life on the Internet, an agent’s entire structure is described by a program “genome.” “Download a genome and it grows a new agent from scratch. Once it’s born, it connects immediately to other agents and becomes a member of the security community. This makes the agent programs easy to deploy in large numbers on the Internet.”

Other members of the Sandia team include Shannon Spires, Hamilton Link, Brian Murphy-Dye, Brad Nation, Pat Gilfeather, and Gabi Istrail.

Work on the program was initially funded by Sandia’s Laboratory-Directed Research and Development program in its “Grand Challenge” called Engineered Collectives. Current funding is from DOE Defense Programs.