LIVERMORE, Calif. — Tim Briggs has built a career at Sandia National Laboratories tearing and breaking things apart with his team of collaborators. Now, he’s developed a fracture-testing tool that could help make everything from aircraft structural frames to cellphones stronger.

Briggs has filed a patent for a device associated with bonded structural composite materials with the deceptively mundane title “Mode I Fracture Testing Fixture.”

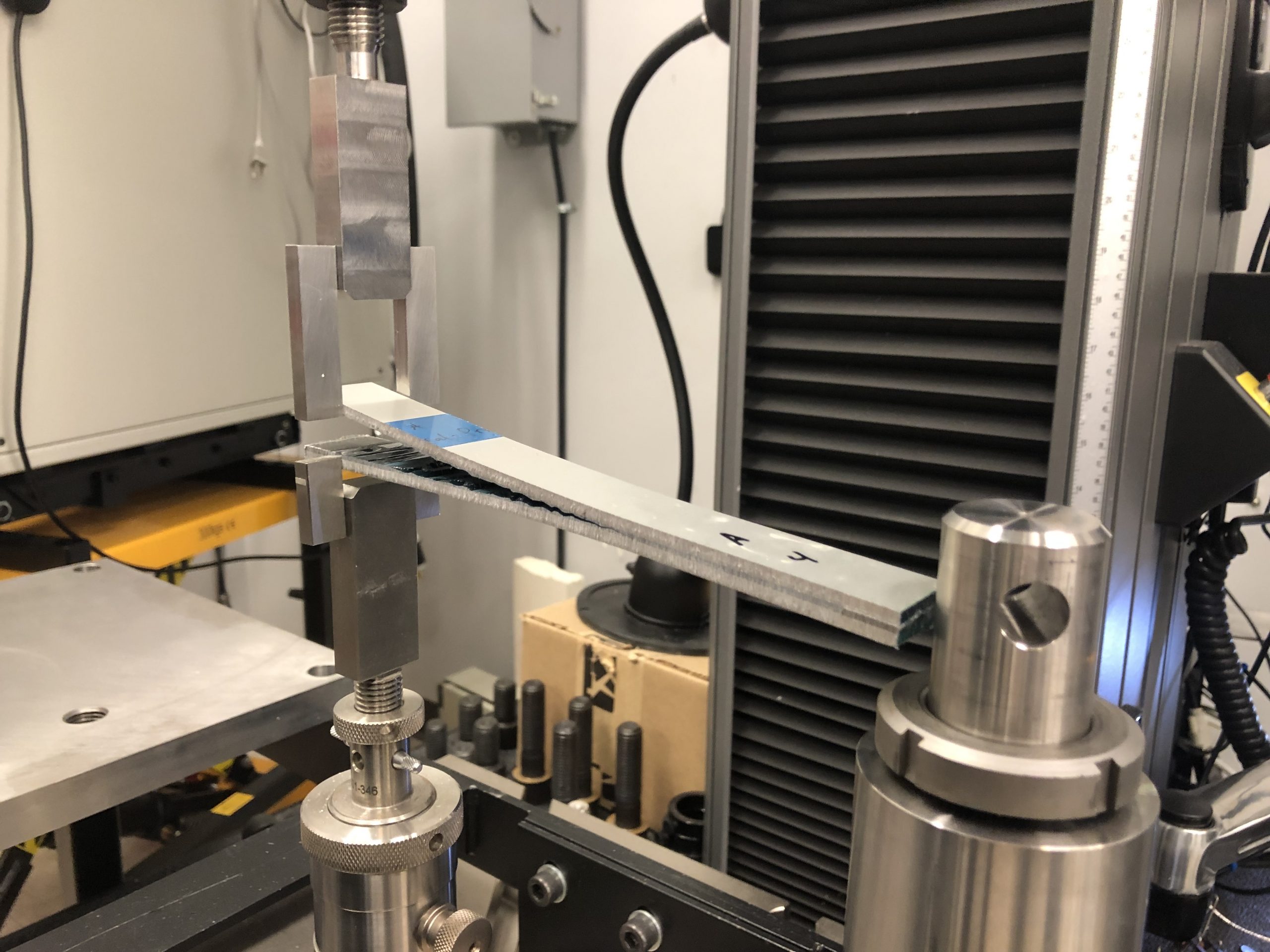

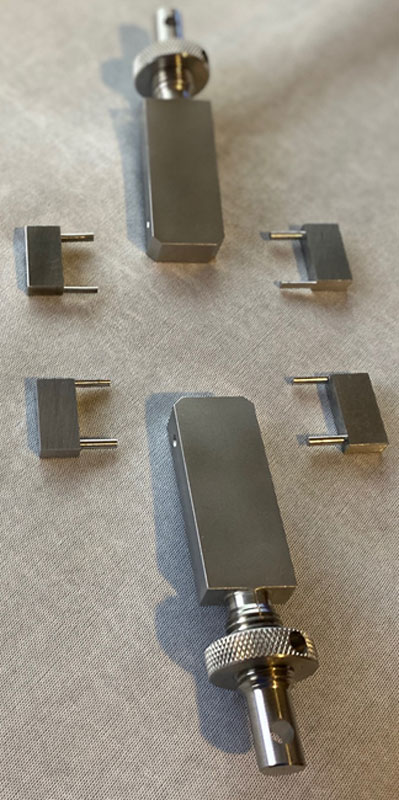

The device, a small set of two hangers no larger than a hand, fits into a precisely drilled hole through the middle of two structural materials bonded together. The hangers then attach to a traditional testing machine designed to pull the bonded sample apart to measure how tough it is. Before Briggs’s innovation, sample preparation and conducting a series of such fracture tests might take days or even weeks longer.

“We pull the fracture specimens apart in a very controlled manner,” Briggs, who works in Sandia’s Lightweight Structures Lab, said. “Then, we’re able to measure the response of the material and quantify the relevant fracture properties, which informs us how cracks might actually grow when used in finished products under various loading conditions.”

In every industry and consumer product, things break. This can lead to property loss, litigation, injuries and loss of life. Sometimes the fracturing happens because a design is engineered without a full understanding of how the materials perform in certain conditions.

“Think about critical applications like a pressurized aircraft at 30,000 feet with 300 or more souls on board relying on bonded surfaces as part of a critical load path,” Briggs explained. “That can never fail. But people also don’t want their very benign carbon-fiber hockey stick or mountain bike that they paid hundreds or even thousands of dollars for to break.”

The device and methodology can be applied “to everything in between — medical devices, aerospace, automotive crash worthiness, civil structures, pressure vessels, recreation and sporting. Every structure is likely affected by fracture-based failure mechanisms, and testing is difficult. This new device and approach aim to make it a bit simpler,” he said.

Before he developed his hangers, Briggs and his team would have to align and bond hinges to the specimens, which added significant time and cost to the process before you could even set up and perform the experiment.

“As simple as it is,” he said of the new approach using the free-rotation hanger system, “this is kind of the novelty of this device. There’s a beauty and simplicity here. Now you can completely abandon the old, laborious process of bonding hinges to the surfaces of the specimen. I can’t tell you how much work it was for us to cut hinges, abrade and clean all the bonded surfaces, mix adhesives, precisely align the hinge to the specimen face, glue the hinge to one side of the specimen, allow it to cure, clean up the mess, then do it all again to the other side. Now it’s literally just drill a hole and go.”

Briggs’ patent-pending device allows for a much quicker and inexpensive turnaround for his team to obtain these critical-fracture properties, which allows for much greater insight into the conditions that could cause materials to fracture and fail.

Because the time for testing is significantly reduced, engineers will have an opportunity to make things better by subjecting samples to wider array of environmental and loading conditions, ensuring more predictable performance to improve reliability and safety while reducing research and development costs.

Businesses can not only make their products safer and more reliable with this new approach, but the cost savings realized in more efficient research and development as well as reductions in liability litigation could be passed on to the consumer.

Briggs said, “I hope this new approach, and the work it could enable for others, can have a broad reach and impact beyond Sandia’s national security mission, touching people’s everyday lives more visibly in their day-to-day activities.”