Download 300dpi JPEG image, ‘biosim.jpg’, 952K (Media are welcome to download/publish this image with related news stories.)

ALBUQUERQUE, NM — In the emergencies of tomorrow — when rescue personnel may need to triage and treat mass casualties following release of a nerve agent in a shopping mall, theme park, or subway, for instance — there will be no second chances. Rescuers who become victims of a terrorist attack can’t save lives.

Soon emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and firefighters may be able to practice responding to such attacks using a virtual reality (VR) training tool under development at the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories.

Sandia computer scientists have combined seven years of virtual reality research into BioSimMER, a VR application that immerses first responders in a 3-D computer-simulated setting — a small airport in which a biological warfare agent has been dispersed following a terrorist bombing. Simulated casualties with a variety of symptoms are found throughout the airport.

BioSimMER can help emergency personnel make better decisions if ever they are called on to respond in a real chem-bio attack, says project leader Sharon Stansfield.

“With virtual reality, you can practice over and over again, like in a video game,” she says. “You make mistakes, you learn. If someone dies, you can hit the reset button.”

Saving ‘cyber casualties’

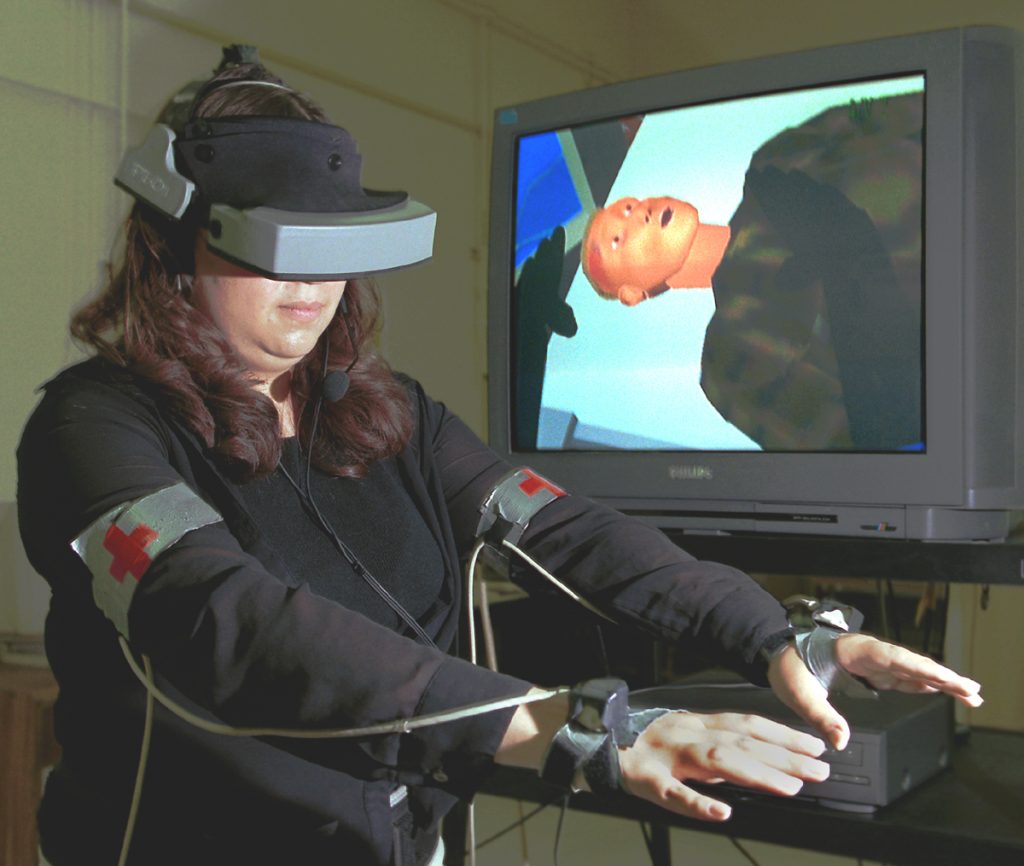

The computer simulation engages the rescuer’s eyes, ears, and decision-making abilities through goggles that display the scene’s images. The rescuer wears sensors on the arms, legs, and waist, allowing the player’s motions to be fed back into the simulation.

The researchers worked closely with Dr. Annette Sobel, a Sandia physician and researcher, to create “cyber casualties” with realistic symptoms and real-time changes in their conditions. One virtual casualty has a visible chest wound. Another has symptoms that indicate head trauma. Another suffers from inhalation of Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), the airborne bio agent used in the simulation. And a fourth appears to exhibit the symptoms of SEB exposure, but closer examination shows him to be suffering from psychological shock.

During a simulation, the player must triage, diagnose, and attend to the medical needs of each casualty. Visual indicators — like a victim’s movements, labored breathing, or skin color — and vital signs — such as blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate — give clues to each victim’s condition. If the rescuer is wrong — or not fast enough — the casualty could die.

After making a diagnosis, a player can administer medical treatment by reaching for and using tools in a virtual medical kit. Players may need to attend to initial decontamination procedures, place masks over a patient’s nose and mouth, or place sensors or other monitoring equipment near the patient. Most important, they need to learn to protect themselves.

“A player who dies a quick cyber death will not likely forget the importance of personal protective equipment in the future,” says Stansfield.

Although textbook-style preparation and live training exercises are valuable pursuits as the nation’s emergency personnel prepare for future emergencies, she says, BioSimMER offers some additional advantages.

“We tend to understand what we see with our eyes and do with our hands,” she says. “The strength of VR is being able to train on things you can’t do otherwise, particularly in highly contaminated or highly stressful situations.”

“We don’t think BioSimMER should replace live exercises,” she adds, “but it can provide an inexpensive way for emergency personnel to practice.”

Achieving a suspension of disbelief

Although BioSimMER’s graphics aren’t as refined as the latest 3-D video games, Stansfield admits, the VR application does offer some realism that video games can’t.

“In video games, the world is imaginary,” she says. “But a VR world is a representation of a real place with representations of real people moving in real time. Everything in that world must move and respond as if it was real and bound by the laws of physics.”

Creating a virtual world with such physical realism does require some tradeoffs, she says, but the ultimate goal is to create a suspension of disbelief. “You’ve got to make the player believe, at least temporarily, that they are in the situation you are presenting to them,” she says.

The airport used in BioSimMER is a fictitious one-story, three-gate airport based loosely on a real airport in central New York. The research team modeled how the airborne biological agent would spread through the airport following an explosion that dispersed the agent.

More than 20 first responders got their first chance to test drive BioSimMER at the National Emergency Response and Rescue Training Center at Texas A&M University in July.

“Those people out there — the police, the firefighters, the EMTs — they do important jobs,” says Stansfield. “They are telling us they want this. If we can do something to help them, then we are using technology to make a real contribution to society.”

Development of BioSimMER was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). BioSimMER also builds on previous Sandia virtual reality work, including applications for training battlefield medics and for law enforcement small-teams tactical training.

Although BioSimMER is a research prototype, not a finished product, the researchers hope to continue development and refinement of the system and scenarios, with the goal of making a version of BioSimMER available to the user community in the not-too-distant future.

Currently, they are working on making the user’s interaction with the BioSimMER virtual world easier and more realistic with funding from DOE’s Office of Science and Technology Pilot Projects in Biomedical Engineering Program.