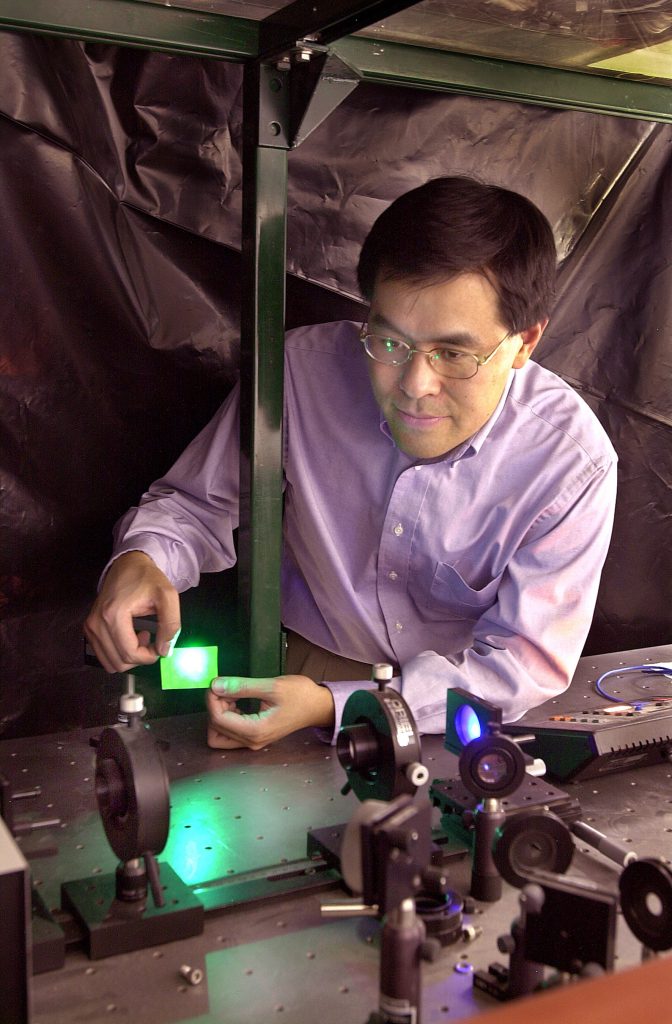

(Photo by Randy Montoya)

Download 300dpi JPEG image, ‘UVvixel.jpg’, 1.5MB(Media are welcome to download/publish this image with related news stories.)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. The first ultra-violet (UV) solid-state microcavity laser has been demonstrated in prototype by scientists at the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories working with colleagues at Brown University.

Among their benefits, UV VCSELS (vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers) coated with phosphors have the capability to generate the white light most prized for indoor lighting — illumination currently provided by gas-filled fluorescent tubes widely used in offices, schools, factories, and by incandescent bulbs used in most homes.

Such solid-state emitters will last five to ten times longer than fluorescent tubes, be far hardier, and perhaps most noticeably, grouped several hundred to a postage-sized chip, will have aesthetic value: instead of a single clunky tube, the chips will be arranged in any configuration one might wish on ceiling, wall, or furniture.

LEDs — light-emitting diodes built on similar principles to VCSELs — in the red range have already replaced ordinary light bulbs in traffic lights and vehicle tail lights.

$100 billion a year in cost savings

Startlingly, successful penetration of the lighting market by LED/VCSEL technology by 2025 “should translate [globally] into cost savings of $100 billion a year, power generation capacity reductions of 120 gigawatts, and carbon emission reductions of approximately 350 million tons year (assuming that all the savings come from coal-fired plants).” The quote, from a white paper presented at the Optoelectronics Industry Development Association in Washington, D.C. in Oct. 1999 by researchers at Sandia and Hewlett-Packard Company of Palo Alto, Calif., continues, “No other major electricity application (motors, heating, refrigeration) represents such a large energy savings potential.”

Says Sandia lead scientist Jung Han, “Many groups are racing to create such lasers in the UV range. It was a dream, yet distant. Now we have achieved it.”

A paper describing the advance appeared in the journal Electronics Letters Oct. 12.

Detects bioweapons, fissionable material

Easily portable UV laser light also interests Sandia researchers because it causes weapons-grade fissionable materials and dangerous E. coli bacteria to fluoresce very efficiently in the visible spectrum, aiding in the detection of attempted thefts and preventing the spread of natural or human-caused epidemics.

“No one before this has achieved the technology to create a compact laser source for UV excitation,” says Han. “It is important for national security because many agents employed in chemical and biological warfare contain molecules which do not respond to longer wavelengths of light.” Current detection methods require adding a chemical “tag” that responds to longer-wavelength excitation. Tagging is time-consuming and expensive.

Current status

Currently, the invention is in the laboratory stage, powered by bigger, more conventional lasers — a method called optical pumping. The next step is electrical pumping, a more commercially useful way to power such devices. This will require developing connectors that will transmit electricity to the tiny lasers. Han expects his group to demonstrate this capability in one to two years.

The process of emitting white light by VCSELS is similar to that in standard fluorescent tubes. The inert gases in fluorescent tubes emit UV as electric current flows through them. These rays strike phosphors that coat the tubes’ inside wall, causing them to emit visible light. The tubes, while superior in many ways to incandescent bulbs, burn out in roughly two years, are breakable, contain poisonous mercury vapor, and are not aesthetic.

Technical discussion

While project work had been ongoing for three years, a key advance took place when the element indium was added to the VCSEL materials mix in August 1999. VCSELS are made of nanoscopically thin layers of semiconductor materials that emit photons when electricity is passed through them. While gallium nitride and aluminum nitride both emit in the ultraviolet range, the efficiency with which those materials make use of input power is not high — perhaps about one percent, says Han. The inspiration of adding indium brought VCSEL efficiency to a tolerable starting point of 20 percent, though it pushed the wavelength emitted longer into the near-ultraviolet range.

“We pay the price for a necessary evil,” says Han.

(The scientific term, “near-ultraviolet,” does not mean “outside the ultraviolet range” but, rather, “close within its borders.” The Sandia VCSEL’s 380 nanometer wavelength is not short enough to cause sunburn — about 320 nanometers — but is smaller than 400 nanometers, the conventionally accepted point of entry into the UV range.)

In addition to being efficient light-emitting mediums, some of the layered materials reflect light from both top and bottom surfaces back into the photon-generating area to facilitate the release of still more light, just as do conventional lasers. The successful synthesis of highly reflective bottom mirrors from aluminum-gallium-nitride was another important factor. Sandia, a leader in developing and improving VCSELS (which now exceed 50 percent efficiency in infrared and red), traditionally has used titanium oxide as a top dielectric mirror layer. But because that oxide absorbs light below 450 nanometers rather than reflects it, it was not suitable as a mirror for UV. Therefore, hafnium oxide is used in this work.

While many possibilities exist to produce white light from semiconductors, VCSELs are a leading contender for several reasons. Blue LEDS already commercially available also give off white light through phosphors, but the light so rendered is considered a cold white because it is overbalanced toward the blue spectrum. Combinations of red, blue and green LEDS can produce white light but may not be cost-effective. VCSELs create a more monochromatic and directional beam.

The work is supported by Sandia’s Laboratory-Directed Research and Development program and by DOE’s Basic Energy Science program.