ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Texas Tech University repeated last year’s victory in the novel design category of Sandia National Laboratories’ annual competition to design new, extraordinarily tiny devices, while Carnegie Mellon University won the educational microelectromechanical (MEMS) prize for the second year in a row.

This year’s contest attracted engineering students from nine universities, nearly double the number of competitors in 2011. The increase was due in part to participation by Mexican universities.

The student designs are blueprints to build mechanical devices in the micrometer size range, to be powered by tiny amounts of electricity.

MEMS devices are omnipresent in modern society. They help inkjet printers and laser disk players to function, probe biological cells, enable high-tech machinery, route telecommunications and much more. New uses for the devices — inexpensive to construct and to operate — continue to be discovered. Some devices are smaller than the thickness of a human hair (about 70 micrometers).

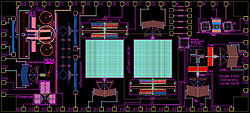

Texas Tech students, who last year won with an ingenious, dust-sized dragonfly with surveillance possibilities, this year designed a micro-rheometer device able to measure the behavior of very thin quantities of liquid, like the synovial fluid in knee joints. The method requires much smaller samples compared to macro-scale rheometers, the standard tool.

“It is much easier, and usually less painful, to obtain small quantities of bodily fluids from patients,” the students wrote in their project description. The project used an advanced design process called SUMMiT V™, created and supported by Sandia, that enables the joining of five layers of silicon to form a complicated device.

Carnegie Mellon students, who last year designed a highly sensitive microvalve for more control over very small fluid flows, this year made use of the relatively large change in mass that occurs when a microdevice adsorbs even a small amount of material. The increase significantly alters any vibrational frequencies of the system. Characterizing adsorbed material this way can say a lot very quickly about what surface changes might occur in the structure under observation. For example, water vapor on MEMS devices may reduce the fatigue strength of polysilicon MEMS, while hydrocarbons adsorb onto microrelay contacts, increasing their electrical resistance.

The MEMS University Alliance, which now has more than 20 members, is part of Sandia’s outreach to universities to improve engineering education. It is open to any U.S. institution of higher learning and select Mexican universities.

The alliance provides classroom teaching materials and licenses for Sandia’s special SUMMiT V™ design tools at a reasonable cost, so universities that lack fabrication facilities can develop a curriculum in MEMS.

Sandia executives, led by Steve Rottler, chief technology officer and vice president of Science and Technology and Research Foundations, and Microsystems director Gil Herrera helped encourage Mexican universities’ participation in the contest, University Alliance Design Competition, by traveling to Mexico to sign memorandums of understanding to promote MEMS science and technology there.

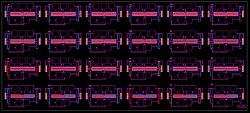

Competing schools this year included the Air Force Institute of Technology, Arizona State University, Central New Mexico Community College, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional of Mexico City, Carnegie Mellon University, Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute, Texas Tech University, Universidad de Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez, Universidad de Guadalajara, Universidad de Guanajuato, University of Oklahoma, University of Utah and Universidad Veracruzana.

“The Mexican universities were highly competitive with the U.S. universities,” said Keith Ortiz, Sandia manager of MEMS Technologies, who along with Gil Herrera hosted the student presentations. “We were impressed by their creativity and use of technology.”

The contest process takes nine months. It starts with students developing ideas for a device, followed by creation of an accurate computer model of a design that might work, analysis of the design and, finally, design submission. Sandia’s MEMS experts and university professors review the design and determine the winners.

Sandia’s state-of-the-art Microsystems and Engineering Sciences Applications (MESA) fabrication facility then creates parts for each of the entrants. The design competition capitalizes on Sandia’s confidence in achieving first-pass fabrication success, which restricts the entire process to a reasonable student time-frame.

Fabricated parts are shipped back to the university students for lengthy tests to determine whether the final product matches the purpose of the original computer simulation.

The University Alliance coordinates with the Sandia-led National Institute for Nano Engineering (NINE), providing additional opportunities for students to self-direct their engineering education, and the Sandia/Los Alamos Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies (CINT), a Department of Energy Office of Science center with the most up-to-date nanotechnology tools.

Travel by students and professors to the awards ceremony was made possible by grants from the International Society for Optics and Photonics. Carnegie Mellon professorial oversight was provided by Maarten de Boer. Texas Tech students were supervised by faculty adviser Tim Dallas.

For more information regarding the University Alliance and the design competition, contact Stephanie Johnson at srjohns@sandia.gov.