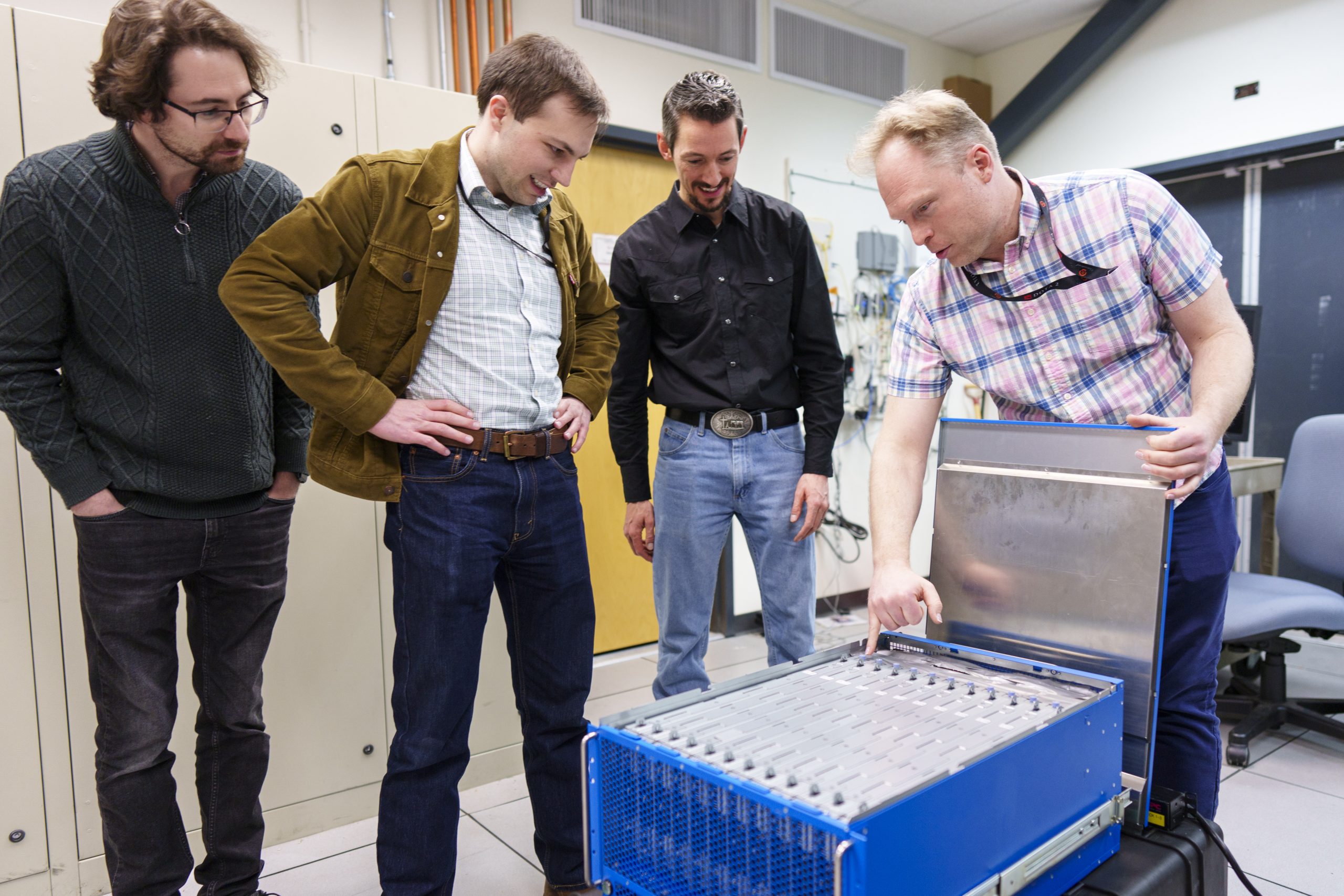

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — In a groundbreaking stride toward the future of computing, early this year Sandia National Laboratories researchers welcomed the arrival of an extraordinary brain-based computing system called Hala Point. Packed with a staggering 1.15 billion artificial neurons — believed to be the biggest brain-based computing system in the world — and cleverly confined within a container roughly the size of a microwave oven, this technological marvel had made its journey to Albuquerque, New Mexico, from its birthplace at Intel Corp. in Portland, Oregon.

The system’s purpose is to provide Sandia and National Nuclear Security Administration research teams with the tools to realize brain-based computing on a large scale. At a smaller scale, the neuromorphic method has already demonstrated greater speed, accuracy and lower energy costs than conventional computing in several labs, including Sandia.

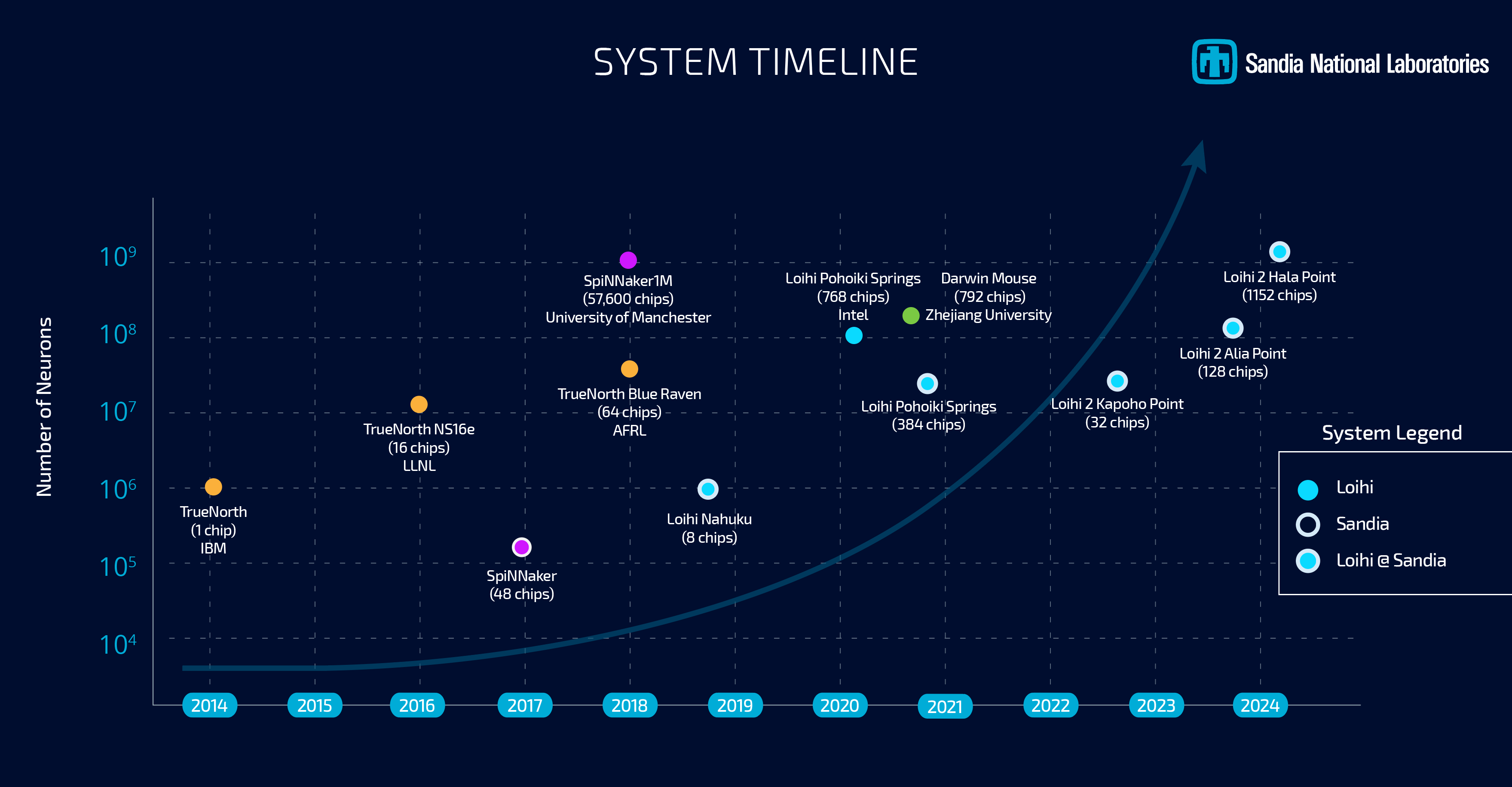

Compared with the system of 50 million artificial neurons (dubbed Pohoiki Springs) received by Sandia from Intel three years earlier, the new system is ten times faster, 15 times denser and has increased from 128,000 circuits on a single chip to one million.

“We believe this new level of experimentation — the start, we hope, of large-scale neuromorphic computing — will help create a brain-based system with unrivaled ability to process, respond to and learn from real-life data,” Sandia lead researcher Craig Vineyard said of the latest arrival.

“Our colleagues at Sandia have consistently applied our Loihi hardware in ways we never imagined, and we look forward to their research with Hala Point leading to breakthroughs in the scale, speed and efficiency of many impactful computing problems,” said Mike Davies, director of the Neuromorphic Computing Lab at Intel Labs.

The two systems use two generations of research chips, code-named Loihi 1 and 2 for the youngest volcano in the Hawaiian Islands. The latest computing system comprises 1,152 Loihi 2 research processors and is named after another Hawaiian location.

Algorithms for a scale previously unrealized

“Since a system of this scale hasn’t existed before, we’ve been developing algorithms to efficiently use it,” Vineyard said.

While his group is interested in problems involving large-scale physics, chemistry and the environment, he says the technique has the potential to be disruptive at multiple scales.

“On the one hand, we’re looking at science codes, physics computations,” Vineyard said. “Can we model large processes in more detail? What about device design, or climate models with better-defined resolution?”

This means, he said, creating applications that can use the full system.

On the middle ground, “We’re not looking at global replacements of all traditional processing,” Vineyard said. “It’s more a matter of identifying the best approach to a problem. A supercomputer that requires the energy of a small city could function with substantial energy reductions if neuromorphic systems took over subsidiary tasks.”

In terms of societal protection, Vineyard sees smarter soldier gear, better analysis of intelligence operations, better border security and quicker response to earthquakes. Medically, he sees more rapid medical diagnosis and less expensive drug discovery.

“We might soon see self-driving cars with neuromorphic technology, lane detection, cell phones with voice recognition, smarter watches and refrigerators, more detailed home security systems. Did the cat run by or is someone in your house?”

Electrical spike that notifies neurons

The neuromorphic process saves energy and compute time by electrically pulsing only when a synapse in a complex circuit has absorbed enough charge to produce an electrical spike. This process discards useless information — that which doesn’t spike — instead of storing it in distant locations and revisiting it in every calculation. In this manner, neuromorphic computing operates like the brain does, with subgroups of active neurons arranged in parallel circuits, tapped for information as needed, rather than the sequential instructions and remote memory storage involving every possible unit that characterizes mainstream computing.

Sandia researcher Brad Aimone said, “One of the main differences between brain-like computing and regular computers we use today — in both our brains and in neuromorphic computing — is that the computation is spread over many neurons in parallel, rather than long processes in series that are an inescapable part of conventional computing. As a result, the more neurons we have in a neuromorphic system, the more complex a calculation we can perform.

“We see this in real brains. Even the smallest mammal brains have tens of millions of neurons; our brains have around 80 billion. We see it in today’s AI algorithms. Bigger is far better.”

Aimone led a Sandia team to an international prize in 2023 for using neuromorphic hardware to suggest solutions to a wide range of problems, including those in heat transfer, medical imaging and finance.

The mismatch: Like running a race in someone else’s shoes

The most obvious difficulties for neuromorphic computing today are that its unique software must either perform through mainstream hardware — a mismatch like running a race in someone else’s shoes — or in neuromorphic hardware typically, though not always, too trivial and lacking in scale and function to produce notable results.

“It’s clear that brain-based computing functioning through conventional serial hardware hampers the efficiency of neuromorphic programs,” Vineyard said.

Aimone added, “For a long time, we’ve been forced to think about neuromorphic algorithms that are small because neuromorphic hardware is new. I fully believe that the advantage of a neuromorphic computer will best be seen at realistic brain-like scales. With this billion-neuron system, we will have an opportunity to innovate at scale both new AI algorithms that may be more efficient and smarter than existing algorithms, and new brain-like approaches to existing computer algorithms such as optimization and modeling.”

As Hala Point prepares to experience its newly minted Sandia programs, the future awaits.

The work is funded by NNSA’s Advanced Simulation and Computing program. The NNSA is a semiautonomous DOE agency responsible for the management and security of the nation’s nuclear weapons, nuclear nonproliferation, and naval reactor programs, as well as responding to nuclear and radiological emergencies in the U.S. and abroad.”