ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Sometime between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago, prehistoric humans took their first steps into Sahul, an ancient landmass made up of modern Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania. But nobody knows which way they went after that.

“One of the really big unanswered questions of prehistory is how Australia was populated in the distant past. Scholars have debated it for at least 150 years,” said Sandia National Laboratories archaeologist and remote sensing scientist Devin White.

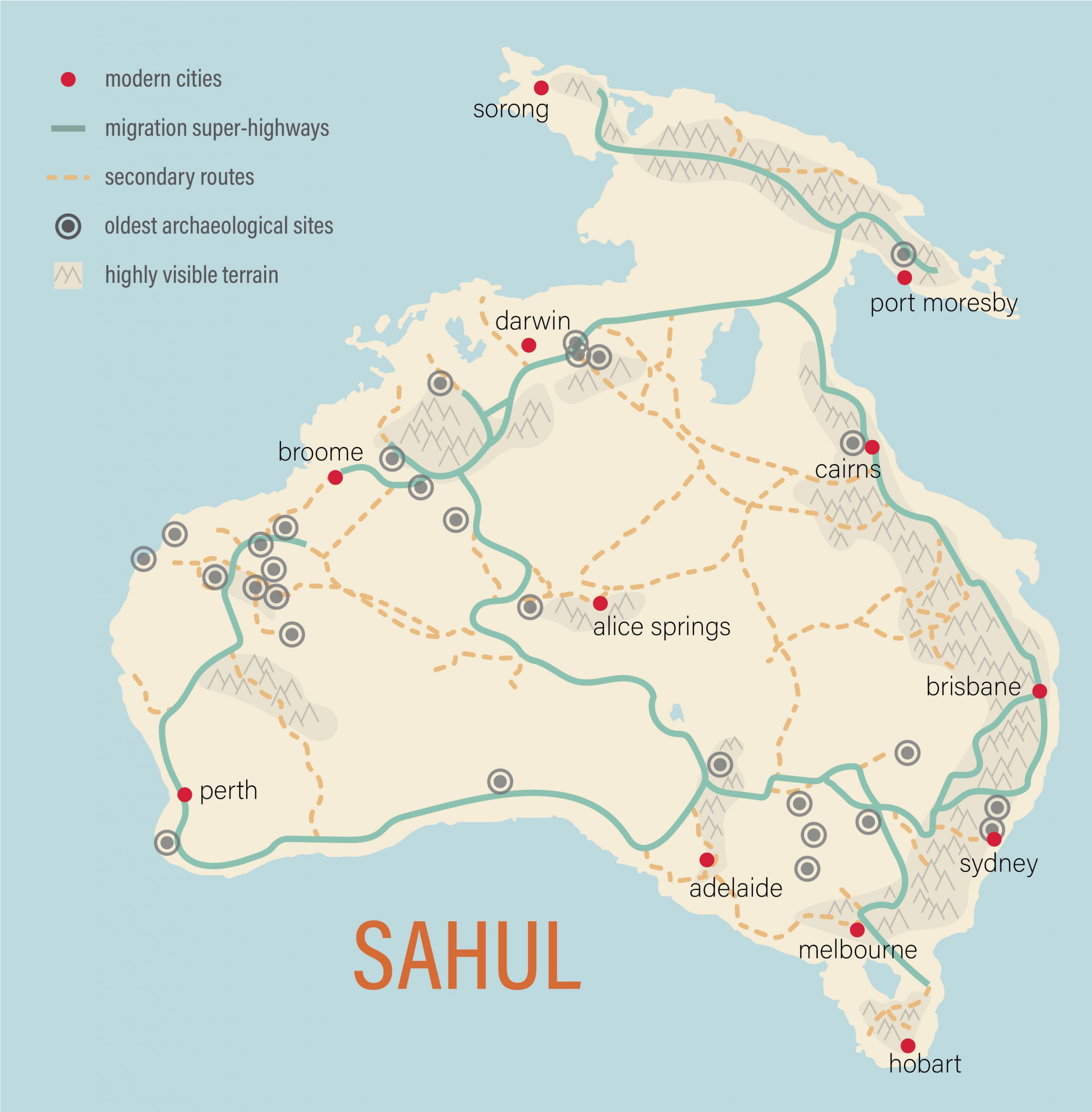

Now, an international team of scientists using a Sandia supercomputer in the largest reconstruction ever attempted of prehistoric travel has mapped the probable “superhighways” that led to the first peopling of Australia. Their results were published April 29 in Nature Human Behaviour.

Their methods could help organizations like the United Nations and the Federal Emergency Management Agency forecast modern day human migration resulting from climate change or sudden humanitarian crises, while the new maps could inform the search for undiscovered archaeological sites. The research team believes it also might be possible to apply their approach to other areas of the world, further illuminating the human story since the first migrations out of Africa about 120,000 years ago.

Powered by 125 billion simulations run on a supercomputer typically used to develop autonomous systems and machine learning technologies, the team’s research is the first high-resolution computational analysis of human migration at a continental scale, dividing the entire supercontinent into pixels 1,640 feet (500 meters) across.

“It is the largest and most complex project of its kind that I’d ever been asked to take on,” said White, who wrote the primary algorithm used, called “From Everywhere to Everywhere,” and overhauled it to program the way-finders. For more than 15 years, White has used geospatial analysis, remote sensing and high-performance computing to study human transportation networks.

Archaeologist and computational social scientist Stefani Crabtree, a fellow at the Santa Fe Institute in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and professor at Utah State University in Logan led the study.

“We decided it would be really interesting to look at this question of human migration because the ways that we conceptualize a landscape should be relatively steady for a hiker in the 21st century and a person who was way-finding into a new region 70,000 years ago,” Crabtree said. “If it’s a new landscape and we don’t have a map, we’re going to want to know how to move efficiently throughout a space, where to find water, and where to camp — and we’ll orient ourselves based on high points around the lands.”

Researchers packed a virtual 25-year-old woman with 22 pounds (10 kilograms) of tools and water and sent her on billions of walks across the continent as it would have looked 50,000 years ago. Her task: find the paths that require the fewest calories to traverse without straying too far from reliable sources of water or from highly visible landscape features like large rock outcrops. The team found that the simulations returned to certain paths again and again, which the researchers dubbed “superhighways,” that line up well with the earliest known archaeological sites on the continent.

Researchers affiliated with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH) also contributed to the project and explained the strong connection between Aboriginal communities, the landscape they have traveled across for millennia and a timeless realm known as the Dreaming.

“Australia’s not only the driest, but also the flattest populated continent on Earth,” said Sean Ulm, the center’s deputy director and a distinguished professor of archaeology at Queensland, Australia-based James Cook University. “Our research shows that prominent landscape features and water sources were critical for people to navigate and survive on the continent. In many Aboriginal societies, landscape features are believed to have been created by ancestral beings during the Dreaming. Every ridgeline, hill, river, beach and water source is named, storied and inscribed into the very fabric of societies, emphasising the intimate relationship between people and place. The landscape is literally woven into peoples’ lives and their histories. It seems that these relationships between people and country probably date back to the earliest peopling of the continent.”