ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Sandia’s one-of-a-kind multiphase shock tube began with a hallway conversation that led to what engineer Justin Wagner describes as the only shock tube in the world that can look at how shock waves interact with dense particle fields.

The machine is considered multiphase because it can study shock wave propagation through a mixture of gas and solid particles.

Shock tubes — machines that generate shock waves without an explosion — have been around for decades. What makes Sandia’s unique is its ability to study how densely clustered particles disperse during an explosion. That’s important because better understanding of the physics during the first tens of microseconds of a blast leads to better computer models of what happens in explosions.

“Not having this correct in those codes could have implications for predicting different explosives properties,” Wagner said.

Understanding how particles move and react in the early part of a blast will help Sandia respond to such national security challenges as improving explosives, mitigating blasts or assessing the vulnerability of personnel, weapons and structures.

The project started when Steve Beresh of Sandia’s aerosciences department and Sean Kearney of the Labs’ thermal and fluid experimental sciences asked a since-retired colleague what he’d like to measure that he hadn’t been able to. He started talking about some of the physics missing from the models used for predicting explosives, “and Sean and I looked at each other and said, ‘We think we could do that,’” Beresh said.

They came up with the idea of a multiphase shock tube that would enable researchers to study particle dispersal in dense gas-solid flows.

The machine was fired for the first time in April 2010. Experiments and diagnostics are complicated, so team members are still gathering data they eventually will incorporate into codes used at Sandia and elsewhere.

“It’s clear that we’ve learned some things that weren’t known before,” Beresh said. “Those physics are important to a code.”

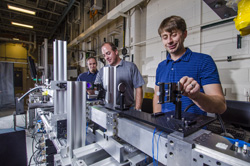

The stainless steel and aluminum shock tube, about 22 feet long, is divided into a high-pressure or driver section that creates the shock wave and a low-pressure or driven section, with a diaphragm between the two. Pressure builds up in the cylindrical driver section and when it gets high enough, the diaphragm ruptures. Spherical particles loaded into a hopper above the low-pressure section flow into the shock tube before the diaphragm breaks, creating a dense particle curtain that’s hit by the shock wave.

The project, initially funded under Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program, hired Wagner to oversee the machine’s design and building. “When we hired Justin we had an empty room and a blank sheet of paper. Now we have a shock tube that is different from what anybody else in the world has,” Beresh said.

Particles in an explosion start out tightly packed. As the explosive process continues, they disperse and quickly become widely spaced. But the physics of the densely packed particles at the start of the explosion are crucial to everything that comes later. They are not yet fully understood, and thus limit current models, Wagner and Beresh said.

“The important thing about the shock tube is it generates a planar shock wave,” Wagner said. “We study the interaction of the shock wave with a dense field of particles to understand the physics relevant to explosives processes.”

Sandia’s machine uses such diagnostics as high-speed pressure measurements, high-speed imaging and flash X-ray to measure gas and particle properties, and it’s adding laser-based diagnostics, team members said.

“We can get different things from the X-ray diagnostics, different things from the laser-based diagnostics, different things from temperature and pressure measurements, and by piecing all of that together we get a better view of the physics that are occurring in the shot,” Beresh said.

The machine’s unique diagnostic capabilities demonstrate Sandia’s ability to collaborate. The team particularly singled out the X-ray expertise offered by Enrico Quintana and Jerry Stoker’s group in the experimental mechanics/non-destructive evaluation & model validation organization. Elton Wright of geothermal research also made sizeable contributions.

The diagnostics required to get useful information from the machine are difficult and expensive, Wagner said. “There’s a reason why it hasn’t been done thoroughly in the past,” he said.

A lot of data for modeling comes from explosions, but it’s difficult to isolate what happens in each part of a blast, Kearney said. “Whereas if you do an experiment like this you can delve deeper into what is really happening,” he said. “But it’s just one piece of the puzzle and they’re all important.”

For more information, visit the Engineering Sciences Experimental Facilities website.