ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — As manufacturers build more wings, fuselages and other major commercial aircraft parts out of solid-laminate composite materials, Sandia National Laboratories has shown that aircraft inspectors need training to better detect damage in these structures.

So the Airworthiness Assurance Center — operated by Sandia for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for the past 26 years — has developed the first course to train inspectors in the airline and aircraft manufacturing industries nondestructive inspection techniques (NDI) for solid-laminate composite materials.

The course was first presented this summer at Delta Air Lines Inc. in Atlanta, Georgia, to 35 engineers and inspectors from six countries. The FAA sponsored development of the course, which is now available to private industry.

“We’re trying to improve the proficiency of these inspectors so that they’re better able to detect damage in composite structures,” said Dennis Roach, a senior scientist in Sandia’s Transportation, Safeguards & Surety Program. “We’re also trying to increase the consistency in inspections across the commercial airline industry.”

By volume, 80 percent of the Boeing 787 and more than half the Airbus 350 by weight are made from composite materials, driving the need for this training, said Stephen Neidigk, a Sandia mechanical engineer and principal developer of the Composite NDI Training Class.

Alex Melton, a Delta manager of quality control and nondestructive testing, said the course began at the right time for his company. Delta will receive the Airbus 350 aircraft next year and the Bombardier C-Series shortly thereafter. Delta plans to have a custom version of Sandia’s course in place for its inspectors.

“This type of class enhances inspector proficiency insofar as it develops the skill of the inspectors,” Melton said. “I think it’s going to be a really good curriculum for our inspectors as we develop the training and integrate it into our training program and, certainly, I think it’s going to be valuable to the greater industry.”

Experiments detecting composite damage showed need for inspection course

For the past decade, Sandia has conducted experiments on the probability of detecting damage in composite materials — honeycomb and solid-laminate structures — that showed wide variations in inspectors’ abilities and techniques, Roach said.

Because many experienced aircraft inspectors started their careers when airplanes were made mainly of aluminum and because composites behave in so many different ways than metal, Sandia recommended the training.

“We saw people not using the exact equipment setup, procedures or methods that would produce optimum inspection results,” Roach said. “They needed customized training that didn’t exist.”

Building on that recommendation, Sandia conducted two workshops in 2014-15, inviting regulators, airlines and aircraft manufacturers from 12 countries to refine the course’s content. The FAA also provided feedback on the course and the design of the NDI Proficiency Specimens used in the hands-on portion of the class, Roach said.

The two-day course covers the properties of composites, the manufacturing processes and the benefits and shortcomings of the materials. Composites produce more fuel-efficient aircraft because they are lighter than metal. Due to the materials’ structures, they are resistant to fatigue and do not crack as easily as metal, in part, because they use fewer joints and fasteners where cracks can originate. But one drawback is that solid-laminates can suffer damage, particularly from impact, that’s not visible at the surface, often because the visible, external surface pops back into place, masking subsurface damage, Roach and Neidigk said.

Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program sponsored two research projects — on the structural health monitoring of composite materials and the development of sensor network systems to assess damage in transportation infrastructure — that produced information that was useful in the course’s development.

Engineered damaged parts based on years of research help inspectors practice

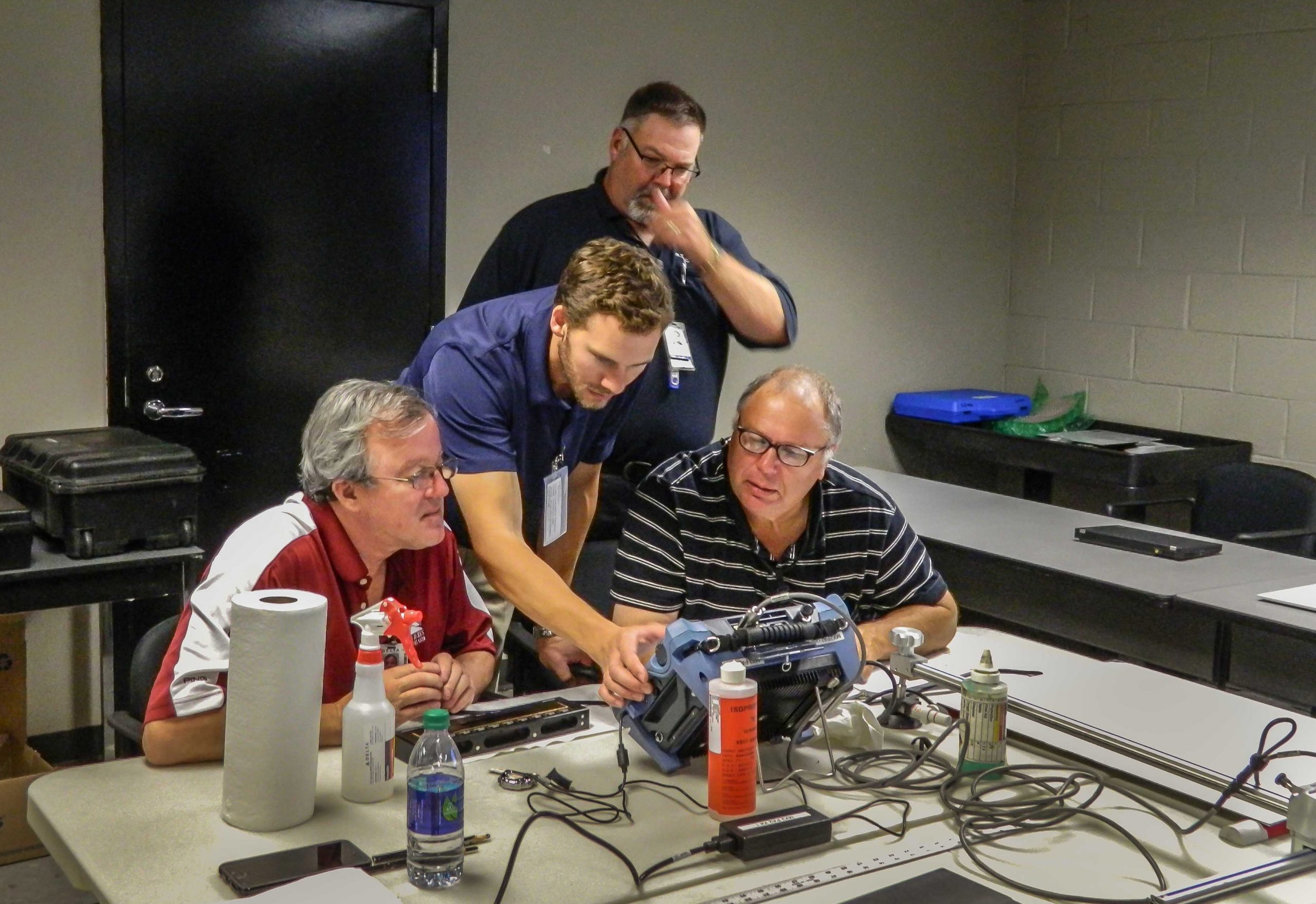

In the course, inspectors learn about nondestructive testing techniques through hands-on exercises. They examine custom carbon-fiber composite samples representing various types of structural configurations common on aircraft, but including engineered defects that range in complexity to fine tune their skills, Neidigk said. The samples were designed and built by Sandia and aerospace company NORDAM in Tulsa, Oklahoma, based on years of Sandia research.

The inspectors set up commercial scanners, including phased-array ultrasonic scanners where they “paint” a two-dimensional image of the composite with ultrasound (C-scan image) to detect damage, and learn to optimize settings to more clearly detect damage, Neidigk said.

They learn how to recognize structural features found in composites, including laminates with substructure, such as co-cured bond lines or tapered laminates, and types of damage, including disbonds, delamination, porosity and impact damage.

The airline industry wants to save time and money by reducing false calls, when inspectors believe they have found signs of damage that is not actually there. An eye-opener for course participants was noticing that the scanner signals decreased in amplitude or intensity due to the presence of acoustic tiles and sealant accompanying composite fuselage panels. These are commonly used to mitigate aircraft vibration noise for passengers. The poor readings on the detection equipment might appear as damage to an untrained inspector, Neidigk said.

But with practice, Melton said, the inspectors learned to discern the effects of the acoustic tiles on the signals generated by the defects.

“One of the most valuable things in our view about this class was the opportunity to practice with these materials because we really don’t get that opportunity and feedback on the aircraft,” he said.

In preparing the course, Sandia engineers recorded the best results they obtained in the lab to identify flaws in the engineered samples and produced flaw maps and grading templates, Neidigk said.

“After the participants have the chance to inspect the panels, we use our grading templates to point out which ones they hit and missed. Then we show them how the reflected signal changed for a particular flaw and why they missed it,” he said.

Roach and Neidigk expect companies to customize the course, as Delta plans, to meet their needs and Sandia will support those efforts as necessary. The team hopes to develop further nondestructive testing courses, particularly to inspect composite aircraft repairs.