ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — In 2023, a team of physicists from Sandia National Laboratories announced a major discovery: a way to steer LED light. If refined, it could mean someday replacing lasers with cheaper, smaller, more energy-efficient LEDs in countless technologies, from UPC scanners and holographic projectors to self-driving cars. The team assumed it would take years of meticulous experimentation to refine their technique.

Now the same researchers have reported that a trio of artificial intelligence labmates has improved their best results fourfold. It took about five hours.

The resulting paper, published in Nature Communications, shows how AI is advancing beyond a mere automation tool toward becoming a powerful engine for clear, comprehensible scientific discovery.

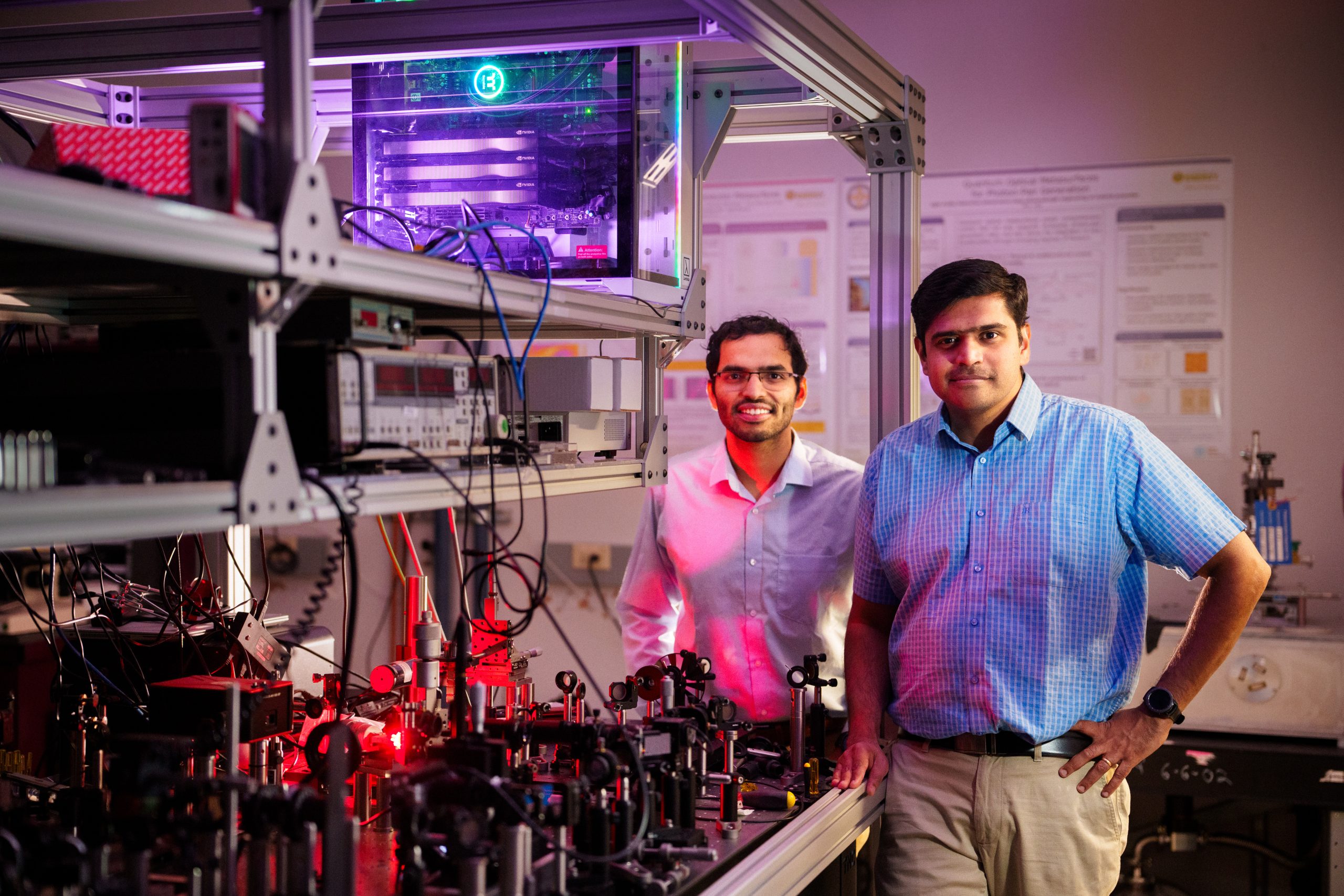

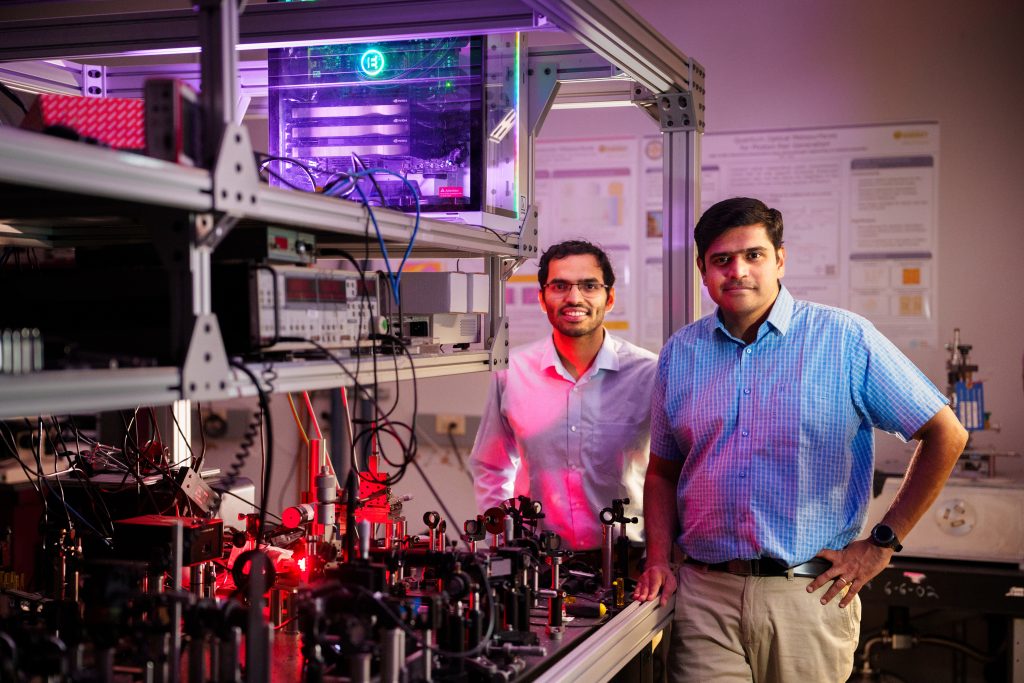

“We are one of the leading examples of how a self-driving lab could be set up to aid and augment human knowledge,” said Sandia’s Prasad Iyer, an author on the new paper and the 2023 announcement.

Research was funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences and Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program. It was performed in part at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, a DOE Office of Science user facility jointly operated by Sandia and Los Alamos national laboratories.

Researchers team across disciplines to modernize lab

A lucky coincidence spurred the research: Iyer got a new officemate.

Saaketh Desai came to Sandia as a postdoctoral researcher. Iyer is an expert in optics, but Desai knew machine learning, a category of artificial intelligence, and had been testing out ways to use it for scientific research. Together, they modernized Iyer’s optics lab.

First, they used a generative AI model to learn and simplify their complex data. Then, they provided this simpler data set to a second AI, called an active learning agent, and connected it to optical equipment. They instructed it to design an experiment based on the learned data, run it on the equipment, analyze the results, and then repeat the process by coming up with a new experiment based on its findings.

After the 300th experiment, which took about five hours, it had significantly improved on what the researchers had spent years developing.

Addressing AI’s black box problem

Even though it was his idea to bring Desai onto the project, Iyer said he had some worries about handing over lab equipment to an AI agent.

“We could potentially do infinite nonsensical experiments without having any meaningful results,” Iyer said.

This is because AI has a black box problem. A query goes in, an answer comes out, but it’s often hard for users to figure out how the AI came up with its answer.

But science requires explanations. When a scientist makes a discovery, they share why they think their discovery works or makes sense. It’s the only way science moves forward — because other scientists can then test that idea to either build on it or disprove it.

Desai also recognized the importance of making sure any AI-based conclusions would be understandable.

“We are constraining ourselves to finding good experiments that will advance our understanding of the domain,” he said. “Therefore, there is a high emphasis on interpreting why something worked or didn’t work.”

Team prioritizes verifiable, AI-augmented research

Iyer and Desai agreed that an AI automaton would not be enough to advance their field. To address the black box problem, they brought in a kind of fact-checker. Maybe unsurprisingly, it was another AI. This one, however, was trained differently. Its job was to figure out equations to explain complex data trends.

The researchers connected this third AI with the second AI in a loop. The active learning agent generated data and worked out its next experiments, while the equation learner attempted to devise a formula to fit the data.

Within moments of finishing the experiments, researchers had new equations in hand to verify that their self-driving lab had found a methodical way to steer spontaneous emission, the kind of light produced by an LED, on average 2.2 times more effectively than they had previously accomplished across a 74-degree angle. Their best results at specific angles showed fourfold improvement.

Surprisingly, the AI had achieved this in a way the Sandia team had never considered. It was based on a fundamentally new way of thinking about how light and materials interact at the nanoscale.

The AI platform’s success is promising for science, said Desai, but it also relies on a lot of computing power, which might not be accessible to every lab. Learning from data was powered by a Lambda Labs workstation with three high-end NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs.

Still, Desai said, he wants to see how far he can take this process. “For next steps, we are generally interested in interpretable optimization schemes and arriving at explainable decisions using AI. We are interested in applying this to the steering problem, as well as other material science problems in general.”