ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Sandia National Laboratories is celebrating 25 years of research conducted at its Z Pulsed Power Facility — a gymnasium-sized accelerator commonly referred to as Z or the Z machine.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, only a limited number of former leaders of the pulsed power program at Sandia will gather Friday to share their experiences with Z.

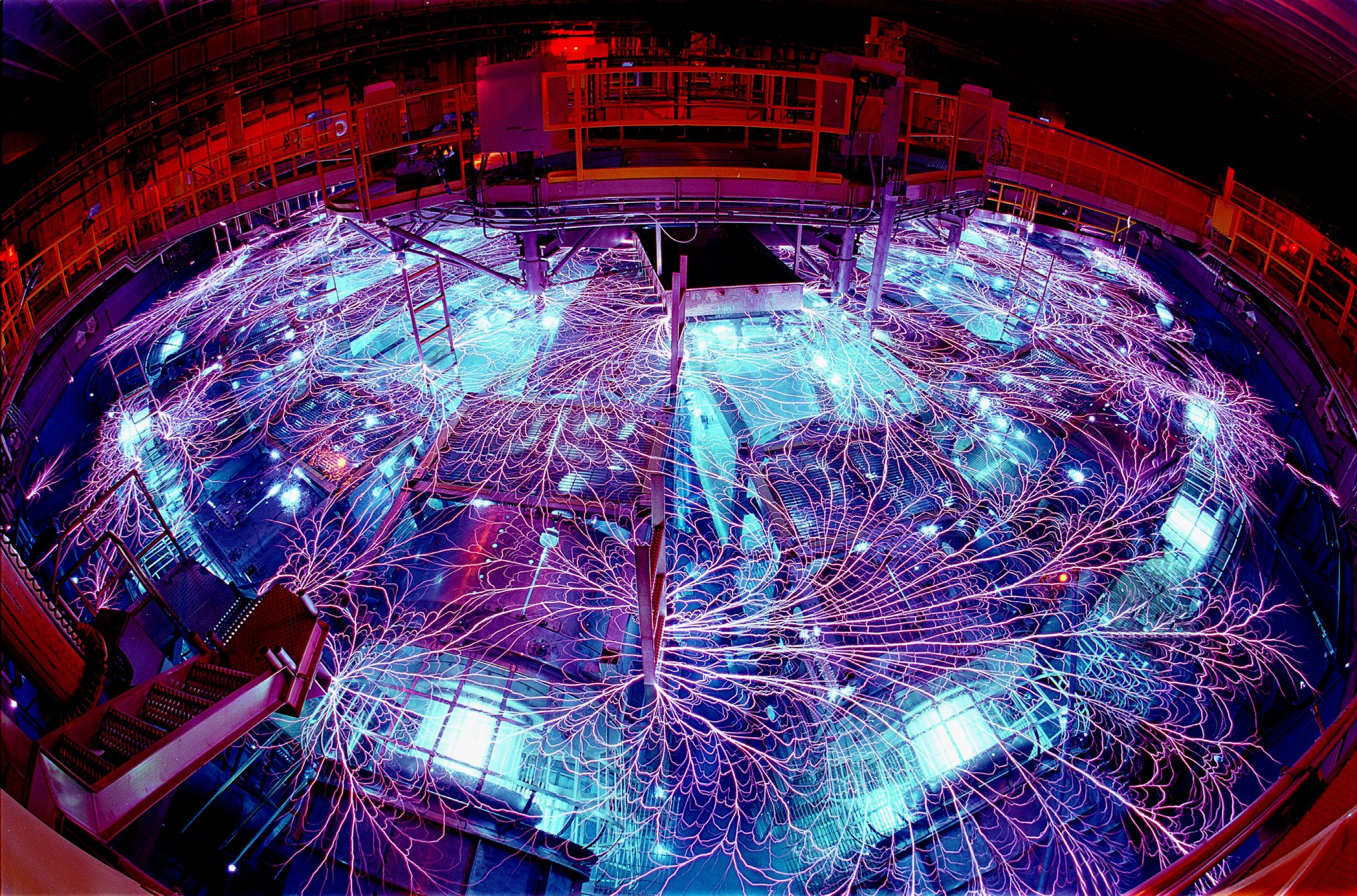

Z began with a simple idea — running large pulsed electrical currents through targets at the center of the machine — that has resulted in startling science even after 25 years.

“We have seen continuous innovation over the history of Z, and we still have about another decade of exciting research lined up,” says Dan Sinars, Sandia’s pulsed power sciences director.

The adventure began 25 years ago, said former director Don Cook, when Sandia researchers modified a machine built in 1985 called the Particle Beam Fusion Accelerator. That machine — Z’s ancestor, in a sense — employed a very high voltage and smaller current to make lithium-ion beams for fusion research. The experimental output was powerful, about 15 terawatts, but had hardly increased in a decade of testing.

So, trying a different approach, the machine was restructured to deliver very high currents and lower voltages. Currents 100 times larger than those in a bolt of lightning efficiently vaporized arrays of tiny wires into clouds of ions. Then the powerful magnetic field accompanying the electric current slammed the ions into each other, a process that emitted copious X-rays that could be used for fusion research and other applications.

The new method, attempted first on a smaller Sandia machine called Saturn, immediately increased the output to 40 terawatts, and led to many experiments to improve the number, size, material choice and placement of succeeding arrays.

“Once it was confirmed in experiments in 1996 on a machine temporarily called PBFA II-Z that enormous pressures (millions of atmospheres) and very high temperatures (millions of degrees Celsius) could be produced by z-pinches, we renamed the machine simply Z in 1996. So, 2021 is the 25th anniversary of Z,” said Cook.

Researchers around the world marveled at the huge output increase, which quickly reached more than 200 terawatts, said former Sandia vice president and early Z leader Gerry Yonas. The Z-pinch work — called Z because the operation occurs along the Z axis in three-dimensional graphs — generated data for the U.S. nuclear stockpile.

Z hasn’t yet created fusion ignition, though the effort to increase its fusion output continues. “Achieving nuclear fusion in the lab isn’t for people who give up easily,” said Sandia fellow Keith Matzen, Z director from 2005-2013 and again from 2015-2019, who cautions it will take a bigger version of Z to demonstrate that the fusion energy emitted by the process is equal to the electrical energy stored in the facility, a milestone known as break-even.

Meanwhile Z researchers have delved into other areas, including determining where life elsewhere in our galaxy may have evolved; investigating the existence of diamonds on Neptune and liquid helium on Saturn; determining the age of white dwarf stars and the behavior of black holes in space; and the amount of water in the universe and its age, said Sinars.

To achieve these unusual capabilities, he said, researchers over decades reimagined work on Z so that the huge magnetic fields naturally accompanying Z’s powerful electrical discharges became instruments in their own right, testing materials by creating pressures exceeding those at Earth’s core or aiding in the effort to create breakeven nuclear fusion by pre-compressing the target fuel environs.

“In the meantime,” said Cook, “Z has become the most energetic source of X-rays for fusion research and for stockpile stewardship on the planet. Its capabilities as a pre-eminent research facility for high energy density sciences are known and appreciated worldwide.”